“There is nothing I would not give, nothing I would not do, to go back to who I was before my diagnosis with PTSD, a condition that I can expect to live alongside potentially indefinitely, and that can only ever be managed. For me, it has proved almost fatal.”

Strong words from any woman. Even more powerful when spoken by a Member of Parliament in the glittering and golden Chamber of the House of Commons in London, England.

“Even at its best, it is a living hell,” summarized Charlotte Nichols, Labour MP for Warrington North, speaking to the Houses of Parliament in May, calling for rescheduling psilocybin in the UK. “I am hopeful that this sort of treatment may offer a light at the end of a very dark tunnel and finally give me my life back.”

Of all psychedelics being considered for legal use, psilocybin appears to be just behind MDMA on the path to legalization: having been granted “breakthrough status” by the FDA in 2018, psilocybin has also been made legal for medical access in special circumstances in Canada in 2022, deemed legal for prescription in Australia earlier this year (and officially legal as of July 1st), and decriminalized or had enforcement radically deprioritized in some form or another in over 11 states and 100 cities in the U.S., many believe that the FDA will approve medical grade psilocybin from start-up Compass Pathways within the next few years. Psilocybin will likely be one of the first legal psychedelics that could “revolutionize mental healthcare,” as researchers, entrepreneurs, and journalists have proclaimed for years.

Yet in the UK, most psychedelics remain in “Schedule One,” deemed to have “no therapeutic value.” This designation was assigned to the drug over 50 years ago, but has not been reviewed despite hundreds of studies published worldwide over the past 20 years demonstrating its potential to support the treatment of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, addictions, traumatic brain injury, and more – all notoriously difficult to treat.

“There is not a single other field where we would accept a 90% failure rate as acceptable, yet in mental health treatment, that is where we are. So why do we set up expert bodies and not listen to them?” continued Nichols, referring to the UK’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), which was first commissioned to review the evidence for psilocybin’s value years ago and pressed by the Home Office to deliver their next report in December 2022 – all to no avail.

“It is dangerous, immoral, and unethical, and it is frankly offensive to both psychiatrists and their patients that we seem to think that, as politicians, we know better because of some moral panic 50 years ago. It feels like institutional cruelty to condemn us to our misery when there are proven safe and effective treatment options if only the government would let us access them.”

By contrast, the addictive and highly dangerous drugs heroin, cocaine, and even crystal meth sit on the “Schedule Two” list in the UK, thanks to their medical utility in extreme circumstances: diamorphine (heroin) is a powerful painkiller, invaluable for the dying; cocaine is a useful anaesthetic (in particular for dentistry thanks to its vasoconstrictive qualities); and amphetamines can reduce hyperactivity in children with ADHD (many drugs have reverse effects in preadolescent brains). The Schedule Two designation makes the drugs far easier and cheaper to research.

“Schedule One classification roughly doubles the cost of research,” says Professor David Nutt of Imperial College London, Director of the Neuropsychopharmacology Unit in the Division of Brain Sciences. “The overall price tag of a license is £15k ($18,441) alone, requiring £5k ($6,147) each for administration, staff time, and security measures, such as installing CCTV cameras for continuous monitoring and storage refrigerators bolted to the floor,” he explains. “Then add an annual renewal cost of around £2k ($2,459) and a staggering £300k ($368,908) price tag for every human study.”

Nutt is considered one of the world’s foremost authorities on the true risks of recreational drugs and the lead author of dozens of ground-breaking studies on the medical benefits of psychedelics, such as the first randomized clinical trial comparing psilocybin to the SSRI antidepressant escitalopram, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2021.

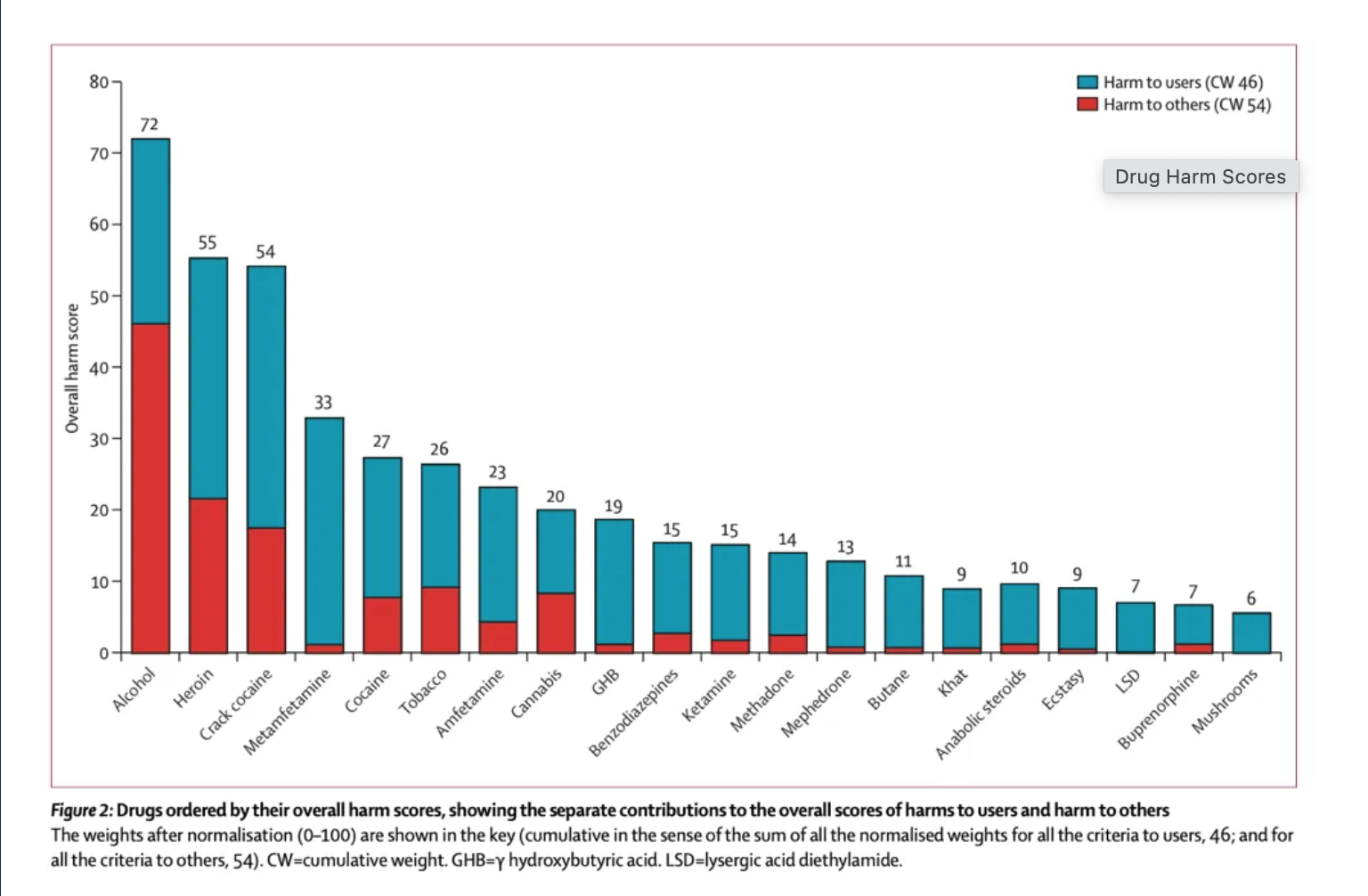

Since being fired by the U.K. government from his role as “drugs czar” with the ACMD for statistically proving that ecstasy is less dangerous than horseback riding, he has become internationally known for his unbiased scientific approach to psychedelic studies. His research focuses on showing the true harms of supposedly dangerous drugs – such as a 2010 analysis published in The Lancet that found mushrooms had the least potential for harm (a finding that other researchers have consistently replicated in the past 13 years), with alcohol (the only legal inebriant) ranked as the most dangerous.

“Yet the Home Office (a department of the British Government responsible for immigration, security, and law and order), simply ignores the scientific evidence for psilocybin’s safety and ignores what a barrier these costs are – it can take over a year to meet all their requirements,” adds Professor Nutt.One extra year may seem trivial, but for some, it is a matter of life and death. An estimated 125 people take their own lives every week in the UK due to forms of depression that may potentially be alleviated with psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. More than 1.2 million adults in the UK are believed to live with “treatment-resistant depression” – the very condition that spurred the FDA in America to grant “breakthrough” status to the company Compass Pathways five years ago for their formulation of psychotherapy-assisted psilocybin therapy.

These mental health conditions come with a hefty price tag to boot: the overall cost to the British economy from depression alone is estimated to be over £10 billion ($12,222,400,000), and the cost from all mental health conditions close to £118 billion ($144,224,320), detracting fully 5% from the nation’s GDP.

“The baffling thing is that it’s so blindingly obvious that we need to reschedule psilocybin,” complains Conservative MP Crispin Blunt, who founded the Conservative Drugs Policy Reform Group in 2018 to campaign for a rehaul of British legislation on all drugs, from magic mushrooms to heroin to nitrous oxide. The CDPRG’s research has shown that once informed about legal access in Canada for those suffering from a terminal illness or intractable depression, Brits, like Americans, overwhelmingly support rescheduling psilocybin: fully 59% are in favor of legal access to palliative care patients, with only 9% against.

Yet, while the public supports legislative change, there is nothing but “bureaucratic inertia” in the government, says Blunt, noting that the Minister of State for Crime, Policing, and Fire, MP Chris Philps (the minister tasked with drugs policy) did not even attend a key debate.

“What are we to make of his absence?” asks Blunt. “There is absolutely no excuse for the government not being able to grip this and for regulatory agencies not being able to enable this. The government can choose to save lives by providing psychotherapy with psychedelics – for which the medical case is undeniable – or they can choose to continue to allow 18 people a day to commit suicide.”

After Psychedelics, Everything Started to Change Immediately for This Military Veteran

One group tragically prone to suicide: military veterans. This population is more likely to die by taking their own lives than in combat. For those in uniform, the inability to process trauma can be notoriously fatal. Let us not forget: One officer died in the Capitol Hill riots of January 2022, but four took their own lives in the months and weeks afterward.

Lance Corporal Keith Abraham served in the British military in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2004 to 2008 before leaving for civilian life in 2012. His wounds ran deep, and nothing seemed to help.

He tried psychotherapy.

“It helped me understand the processes I was going through, which was valuable – but it didn’t heal my trauma in any way,” he says. “But for some, having to revisit traumatizing experiences over and over in talk therapy is counter-productive – therapy itself can be traumatizing.”

He also tried SSRI antidepressants “multiple times,” but they did little for him. “In fact, they often made things a lot worse – I’d rather be in pain than be numb,” says Abraham. “SSRIs only manage symptoms to help you with day-to-day living – but they can never truly heal you.”

American friends in LA suggested he look into ayahuasca, helping him to travel to Peru in 2014 for the ritual.

“Everything started to change immediately – and I mean immediately. It was incredible,” he says. “It healed my trauma for sure – but I knew I still had work to do and that many of the other people whom I had shared my combat experiences with were suffering just as badly as me, if not worse, and they also deserved the chance to do this.”

Five years later, in 2019, he founded the non-profit Heroic Hearts UK to help veterans access ayahuasca and other psychedelic therapies in countries where they are legal, such as mushrooms in Jamaica and the Netherlands or ayahuasca in many South American countries.

“We all deserve a shot at healing, no matter what we’ve done,” he says.

There is no telling when the UK may reschedule psilocybin or any other psychedelic, so for now, Heroic Hearts can only continue to help fund trips overseas. “We’ve waited this long – and clearly, we’re going to have to wait a little bit more,” he says. “In the meantime, we will just have to do our best.”

Psychiatrist Dr. Lauren MacDonald is another Brit working to bring people overseas for psychedelic therapy after it changed her own life. But while Abraham’s combat trauma is a story many understand, Dr. MacDonald’s tale is less so. Diagnosed with stage four melanoma at the age of just 29 in 2014, she was told that because her specific kind of cancer does not respond to chemotherapy or radiation, there was no treatment. She would likely die before the age of 30.

She spent two years tortured by sleepless nights, unable to think of little else but her impending death.

Thankfully, she was invited to partake in a clinical trial with the Nobel Prize-winning drug Keytruda. It saved her life, reversing the cancer completely. Yet after being told she was cancer free in 2016, she still felt crippled by the “debilitating fear and anxiety around death,” as she puts it. “After having my mortality shown so dramatically to me, I still had the existential dread of the cancer coming back.”

Dr. Macdonald – who had never even heard of psychedelic therapy – was inspired to try psilocybin for her “existential grief” after watching a TED talk by Dr. Roland Griffiths of Johns Hopkins on “The science of psilocybin and its use to relieve suffering.” There are no legal psychedelic healing centers in the UK, so she traveled to Holland in 2018 for therapy. In the Netherlands, mushrooms have been in a legal gray zone for many years, paving the way for a number of psychedelic therapy centers to serve psilocybin-containing truffles (also known as Philosopher’s Stones), which are fully legal despite containing psilocybin like other “magic” mushroom forms.

The experience exceeded all her expectations, she says.

“After coming face to face with my own mortality, there was just so much to unpack around cancer and death: Why am I alive? Why are any of us alive? What is all of this really about? And I realized that much of the anxiety and sadness I was still carrying were centered around the finality of death. But with the psilocybin therapy, I could finally, cathartically, let out all the emotions I had suppressed, and it all helped me to look at death in a different way. I no longer have the fear of cancer coming back. If it does, it will be sad and challenging, but I don’t have the same fear of the finality of death.”

But more valuable than shifting her views on death, she says, was how the experience shifted her views on life. “It really has changed how I lived – I have such a reverence for the mystery of life I didn’t quite have before.”

Dr. MacDonald – now a fully qualified psychiatrist – recently joined the team of researchers in the psychedelic department at Imperial College London under Professor Nutt.

Inspired by cases like Dr. MacDonald’s, palliative care nurse Rosanna Ellis has set up the charity Essence Medicine to help others travel to the Netherlands. She says psychedelics-assisted therapy can “help people die with more peace and dignity.”

Dr. MacDonald and Ellis are also working to help nationally upscale the other services required for psychedelics to truly work. Their current focus is on training large numbers of qualified therapists, as well as improving support and follow-up care for patients.

“Everyone is so focused on the drugs, but what we really need is the infrastructure to make sure people are trained properly and that all the patients are really supported emotionally,” she says. “So many patients report that their physical care for a life-threatening illness was exceptional, but that the emotional, spiritual and psychological elements of their suffering were totally neglected.”

A Rescheduling Catch-22

The “blindingly obvious” case for rescheduling in the U.K. has drawn widespread support across the political and cultural spectrum, from Heroic Hearts and Essence Medicine (patient-led activist groups who are next to impossible to argue with), the CDPRG (linked to the Conservatives, a party hardly thought of as revolutionary), to the Royal College of Psychiatrists (as buttoned up as it gets), to seemingly inoffensive pharma start-ups such as Compass Pathways (seeking acceptance by mainstream medicine), to corporate venture capitalists (where it’s all about the bottom line), to the populist Psilocybin Access Rights campaign, launched at the unabashedly hippy flower child love-in Medicine Festival last summer (so devoted to the virtues of plant medicine they refuse to sell alcohol).

The most frustrating thing, say British campaigners, is they are asking for the most minimal of changes. “All we are actually trying to do is clear barriers to research,” says Blunt, pointing out that if research is prohibitively expensive, it is next to impossible to provide the evidence required for rescheduling. “It’s a catch-22.”

While reformers in other nations seek full legalization complete with regulations and taxation, or more loosely defined forms of decriminalization, British charities are only asking to reschedule the drug for research purposes – it would remain unchanged in criminal matters, designated Class A.

“We have a political culture of taking baby steps and approaching things from an angle of evolution, not revolution – so this measure is really just dipping a toe in the water,” explains Sam Lawes, Outreach & Communications Manager for the CDPRG. “This is not an attempt to ‘move fast and break things,’ and this is not a conversation about the recreational use of drugs. This is a conversation about medical utility and the NHS’s ability to prescribe the best available medicines. It’s such a small request – and they could reschedule this in weeks if they chose to.”

He’s not being hyperbolic: in 2018, the government rescheduled cannabis in just a few weeks in response to demands for the legal prescription of Epidyolex for children with severe epilepsy.

“So while in Britain politicians are sitting on their hands, the Americans, Canadians, and Australians will all likely have legal access to medical-grade psilocybin in the next two years,” complains Lawes.

This begs the question: why is the UK lagging behind other nations like the U.S., Canada, and Australia? Surely, UK citizens deserve the same access to new potential tools to fight dangerous mental health crises like suicidal ideation, PTSD, and depression. Perhaps, once the researchers and medical experts busily trying to solve the psychedelic puzzle have finished, the politicians will finally get off their benches and do the kind of work the U.K. deserves.

The next part of this four-story series explores the human costs of psilocybin prohibition in Canada, and how one man fought tooth and nail for access to psychedelic medicine.