In a time when climate change is melting the Arctic and setting California on fire, rainforests continue to be razed in Indonesia and Brazil, and plastic pollution chokes the oceans, it can still come as a shock that illegal hunting of wild animals for profit is still one of the biggest drivers of extinction. Demand for ornaments such as elephant ivory carvings, fabled tonics such as tiger bone wine, traditional medicines such as ground rhino horn for rheumatism, and exotic household pets such as cheetahs, continue to consign some of the most charismatic animals on earth to a grisly fate.

“There is still an enormous market for chimpanzee body parts in Africa – for example in Nigeria a chimpanzee head will sell for $100 in a market,” says Dr Liz Greengrass, head of conservation for environmental NGO Born Free. “We know that it’s the fetish market, and not demand for meat, that is driving the hunting of chimpanzees in some parts of West Africa – there is still a taboo against eating chimp meat in much of the region, but people who can afford to spend money on ‘fetishes’ will still do so, for use in ‘juju’ or traditional medicine.”

Criminal networks make big money from poaching

Arcane as it might seem, there is one simple reason for the continued trade in wildlife products, says lawyer Shruti Suresh, campaigner with the Environmental Investigation Agency: enormous profits. “Once you have profit associated with any product – and we are talking about very high profits – that will inevitably attract criminality: a toxic blend of organized crime and systemic corruption,” she says.

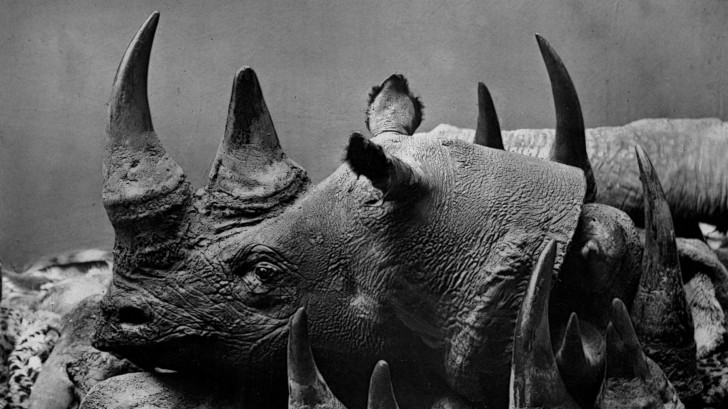

When a kilogram of rhinoceros horn can fetch as much as £50,000, driven by rising demand from China, it’s no surprise that organized crime networks get into the game. Where contraband items reap huge prices, syndicates follow. The rise in rhino poaching over the past decade has been alarming: Between 2007 and 2014, rhino poaching in South Africa increased by a staggering 7,000%, from just 13 animals in 2007 to 1,215 in 2014. That has declined just slightly, to 1,028 rhinos shot in 2017, but the damage has been done: the last male northern white rhino died earlier this year, making the species functionally extinct.

Of the five remaining species, there are still roughly 20,000 white rhinos in Africa and roughly 5,000 black rhinos, but as long as there is demand for horn in China, poachers will persist in pursuing them. Even zoos seem incapable of keeping rhinos safe: last year in a Paris zoo a male white rhino was shot by armed intruders, who shot it three times in the head and hacked off its horn with a chainsaw – despite the presence of security.

Just this month, investigators revealed a tiger farm in the Czech Republic linked to Vietnamese criminal networks supplying wealthy Chinese consumers with bones for wine and glue. With price tags of £50 a gram for tiger bone, £90 a claw and £3,500 for a pelt, it’s should come as little surprise that illegal tiger farms exist. But what is truly shocking is their scale: it’s estimated that farms in China, Laos, Vietnam and Thailand hold up to 8,000 captive tigers – dwarfing the 3,500 estimated to be left in the wild. These farms perhaps counter-intuitively do not discourage hunting of wild tigers: they increase demand by normalizing the trade in tiger parts, and what’s more, it’s cheaper to kill a wild tiger than rear one in captivity. What’s more, we’re now seeing jaguars and lions being poached from South America and Africa to fuel Chinese demand for bones of big cats.

China to lift ban on tiger bone and rhino horn

And if this didn’t already make for grim reading, just in October 2018 the Chinese government shocked the world by announcing it would lift the ban on the use of tiger bone and rhino horn products in traditional medicine. “These enormous tiger farms have been around since the 1980s – the government has succumbed to industry pressure by lifting the ban, and in so doing has rung a death knell for tigers and rhinos,” says Suresh. “This will only drive poaching – we know that tigers will be poached in India, the world’s largest tiger state, and trafficked through Nepal before being sold in China.”

And if 1,200 rhinos poached in a year, or 8,000 captive tigers in farms raised for slaughter sound like enormous numbers, consider that an estimated 50,000 elephants are poached every year for their ivory, according to the Center for Conservation Biology.

When it comes to protecting animals from poachers in the first place, figuring out where illegal hunting is taking place, or identifying the source of an animal product, conservationists face many challenges. But developments in technology are putting new tools into the hands of the law enforcement officials and conservation biologists who so desperately need them, using artificial intelligence, machine learning, unmanned aerial vehicles (or drones) and more.

How science is fighting poachers

One difficulty faced when illegal bones, horns and skin are seized is knowing where they came from – such as a protected area in another country. Fortunately there are ways that artificial intelligence can help: every tiger has a unique stripe pattern for example, like a fingerprint. Using camera traps throughout protected ranges, India has created the world’s database of images, which has been successfully used to determine that a seized tiger pelt came from a protected area and thus had been poached, not farmed. “This is hugely valuable for enforcement,” says Suresh, noting that in 2016 the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) adopted a proposal calling on all member states to share their images of tiger skins to create an even larger database.

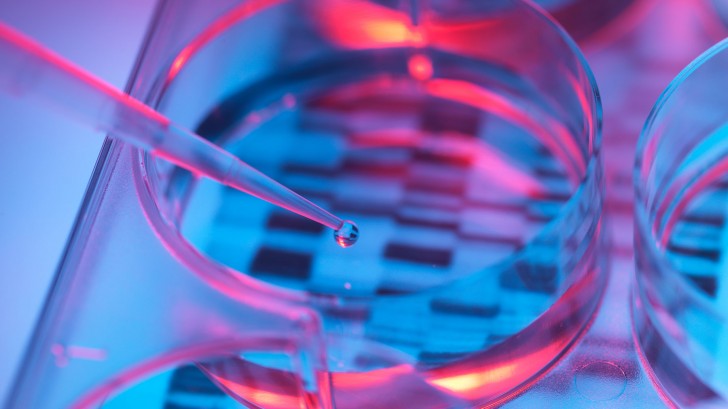

When animal products cannot be identified by appearance alone, DNA analysis can pinpoint the source, and since 2013 CITES has called for any seizure of ivory larger than half a tonne to be sent for DNA analysis. In 2015 biologists from the University of Washington, working with investigators from Interpol, showed in 2015 that a seized batch of ivory had come from two areas in Tanzania, allowing for pressure to be put on the African nation to clamp down on elephant poaching, which had led to the number of elephants in that country dropping by 60 per cent between 2009 and 2014.

Synthetics

Taking a different approach is materials scientist Professor Fritz Vollrath of the University of Oxford, who spent decades studying the properties of spider silk and other biological materials before turning his attention to ivory: working with researchers in China to develop a synthetic mimic of natural ivory. “Ivory is a nice material that people like to handle – but does it have to come from a dead elephant? What if we can create a mixture of collagen and minerals that has the same qualities?” he says. “When we started this project, it was to disarm the carvers lobby in China, who were arguing that they had been carving for 6,000 years and the west was trying to rob them of their traditions. We argued back that we could give them a synthetic material with the same properties, and give it to them in much bigger blocks which they could do so much more with.”

In a similar vein, startup Pembient is trying to produce a synthetic form of rhino horn. They’ve created a few prototypes, and expect to have a pilot run of 1 kg cylinders (roughly 9.93 cm dia. x 9.93 cm tall) at $2.61 per gram ready for sale in 2022 says Matthew Markus of Pembient.

Camera traps

It will take time for synthetic substitutes to catch on, and wildlife protection officials continue to struggle to monitor enormous national parks. To help them, astrophysicist Claire Burke of Liverpool John Moores University in the UK is applying her expertise from studying the stars to track wildlife in the bush with thermal cameras that pick up infrared heat.

“Ecologists told us they were having a hard time coping with all the data from the drones they were using to keep track of their huge territories,” she says. “Well, we’ve been using various tools to look at huge amounts of data like this for decades – just like stars, animals are just bright, shiny objects in a dark background.”

Combining her astrophysical training with conservation biology – a field she dubs “astro ecology” – Burke is using machine learning to improve the accuracy with which cameras can correctly identify wildlife. The best tool to inform the algorithms isn’t technological, however, but human, a “citizen science” project run through Zooniverse that calls on volunteers to identify images of the animals to feed the cameras.

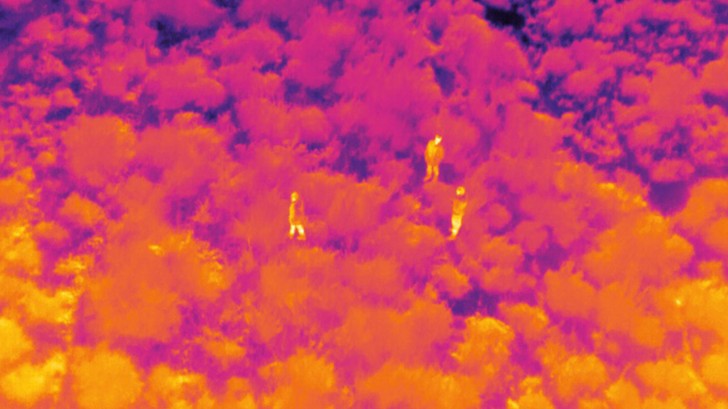

Using an algorithm, this camera can identify humans and different species in thermal images © LJMU/Chester Zoo“Every different species of animal has a unique thermal profile, like a fingerprint. But we need lots of thermal images of the animals in order to learn their thermal profiles – the cameras can’t learn it from just one detection,” she says. “But people are very good at seeing these kinds of patterns. Anyone can volunteer to identify the different animals for us, which we can use to train a computer based on their classifications – after a while the computer can learn on its own and we don’t need people anymore.”

At the end of the day however, images are just images – what conservationists really need to be able to dismantle traps, catch poachers in the act, and effectively monitor territories to prevent poachers from getting near animals in the first place.

Wildlife security

The solution that Founding Co-director of the University of Southern California Center for Artificial Intelligence in Society [CAIS] Professor Milind Tambe came up with is to apply the tools he developed in his work as an artificial intelligence researcher in security applying game theory. “The goals are different, but there is a lot of overlap in the two fields,” he says.

The system he developed to catch poachers, called PAWS (for Protection Assistant for Wildlife Security), grew out of a collaboration with the Uganda Wildlife Authority in 2013, who gave to CAIS 14 years worth of data on poaching activities in Queen Elizabeth National Park, featuring more than 125,000 observations on animal remains, traps and snares and more – all with GPS coordinates. Tambe and his team of students were able to create a system that would predict likely hotspots for poaching and direct patrols there to remove traps before they can kill any animals, plus generate new patrol routes to areas that were infrequently monitored.

“Showing results in the lab is not satisfying for anyone – we needed to be able to test our system in Uganda to show it could work,” he says. “Sure enough, when we asked patrols to monitor areas for a month where the data predicted they could find snares but where they hadn’t thought of going, indeed they did find snares and a poached elephant.”

Continuing to refine the program, Tambe is now partnering with SMART – a consortium of wildlife agencies – to integrate PAWS into their software. “My job is to support conservationists, and to see what I can do for them,” says Tambe.

“In many protected areas in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the protection authorities have to be incredibly resourceful – the funding they receive to monitor huge provinces is the equivalent of what is given to monitor Hyde Park,” says Jonathan Palmer, Executive Director of Strategic Technology at the Wildlife Conservation Society, which is using PAWS to support SMART. “The odds are stacked against them. It’s a tough job, and it’s not rewarded well. Working with Milind’s team, we could figure out how we could use that data with some predictive intelligence that could tell us with some measure of certainty where poaching was likely to occur. From what we see, it provides a powerful tool to suggest where patrols need to go.”

For Tambe, PAWS is just the start.“I find it so interesting, and inspiring, that people who could have led a very comfortable life doing anything else are risking their lives, going off into some forest, and willing to spend the rest of their lives trying to protect wildlife from disappearing,” says Tambe.