The only thing perhaps more shocking than the scale of the Alberta tar sands operation is the ignorance of it beyond Canada’s borders. The lack of awareness of one of the most ecologically destructive and climatically dangerous projects in the world is one of the biggest obstacles to those trying to oppose it.

But even those who are aware of the size and scope of what is considered the largest industrial project in the world are still profoundly unable to grasp that they too contribute to it, in one way or another. It’s incredibly difficult to wrap one’s mind around.

In other words, one of the ultimate barriers is neither political, nor social, nor economic: it is psychological.

I am sitting in the Kilmaforum09 alternative climate conference in Copenhagen on Friday evening. I have just surveyed a dozen people sitting near me – activists, journalists, students, and representatives from NGOs. I questioned only Americans.

“Who do you think is America’s largest source of foreign oil? Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Venequela, Mexico, or Canada?”

Not a single one got the answer right: Canada.

I was prompted to make the survey after an interesting conversation with the head of an American NGO. He had just returned from the Bella centre – the official UN conference that I had been unable to attend (like the overwhelming vast majority of journalists worldwide). Curious to know more about the atmosphere inside, I asked him about his day – and about Canada’s obstructions at the talks. He was aware of the tar sands, and their role in Canada’s economic and political policy.

“But as I understand it, they’re still a small portion of Canada’s emissions and energetic output, though, because it’s still such an expensive process,” he said.

But Canada is the largest supplier of foreign oil to the US, I pointed out.

“No, it’s not. It’s Venezuela or Saudi Arabia, but definitely not Canada,” he placidly said.

Certain I knew my facts – that Canada has been the largest supplier since 2007 – I looked it up. Here they are, the US Government’s own figures.

I then quizzed everyone with an American accent around me – people who, having come to Copenhagen, would be reasonably well-informed regarding climate and energy issues. But each was unaware, and each was surprised at the truth.

“But that’s because of the country’s proximity to the US – it’s just crude being pumped down from the Arctic, like we have in Alaska,” one volunteered.

No, I gently corrected, it’s largely because of the tar sands, and showed them a handful of photos from the world’s largest industrial project.

Then I rattled off the basic statistics: Alberta boasts the world’s second largest reserve of oil – not liquid crude, but a mixture of bitumen and sand. This is difficult to extract, and uses four barrels of fresh water to produce one barrel of oil. This water is left irreparably contaminated with heavy metals and petrochemicals and collected in giant tailing ‘ponds’ – considered by some to be the largest man-made objects ever created.

The production of this oil releases up to five times more greenhouse gases per unit than conventional extraction, and is one of the main reasons that Canada sits almost 30 per cent above its 1990 emission levels (when Kyoto meant we should have at least achieved a six per cent reduction). And official government estimates of the emissions don’t include the fact that the boreal forest – a carbon sink – has to be removed to get at the sands.

Covering an area the size of England the tar sands, if fully developed, could be the factor that becomes ‘the tipping point’ for ‘runaway’ climate change.

“When I first heard about the tar sands in April, to be honest, I was sincerely embarrassed that I hadn’t heard about them,” says Jess Worth, founder of the UK Tar Sands Campaign.

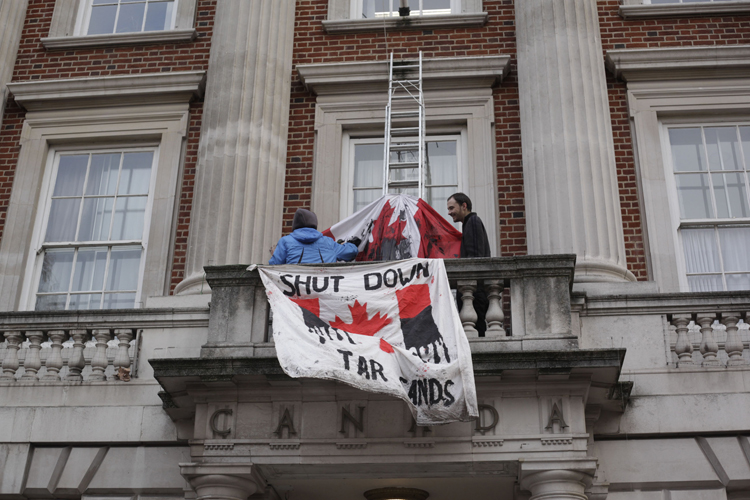

But she needn’t have been embarrassed – this strange lack of awareness is a global norm. But that is slowly starting to change in the UK, where the UK Tar Sands Campaign is now staging protests against the Canadian High Commission and British financial institutions invested in the sands.

At a panel held at Klimaforum last week, Worth, Eriel Tchekwie Deranger, the Freedom from Oil Campaigner for the Rainforest Action Network (and from Fort Chipewyan, a community downstream of the sands), Clayton Thomas Muller of the Indigenous Environmental Network and Maude Barlow, Chairperson of the Council of Canadians, spoke about the scale of the tar sands, how political opposition can be leveraged in Canada, and how public campaigns in Britain could be replicated in other countries.

During the question and answer period a Canadian audience member asked why awareness of the tar sands seemed so much greater in Britain than in Canada.

I raised my hand – I felt this was the one point I could speak to best out of anyone in the room, being a Canadian environmental journalist and a resident of the UK for the past four years. I felt obliged to correct her.

I have spoken about the sands and their impacts at great length for the entire time I have lived in the UK, and no matter how many times I rattle off the statistics they almost always fail to have a lasting impact.

I am convinced that this is due to the way that Canada is perceived: we carry a reputation for being green, liberal, polite and peaceful. Liberalizers of marijuana rights, legalizers of gay marriage, founders of Greenpeace, stewards of the environment.

Canada in fact has an environmental track record far from boast-worthy. But our falsely ‘green’ reputation precedes us, allowing us to carry out destructive environmental practices – from uranium mining to over-fishing to the deployment of intensive mining operations worldwide.

For this reason it has been incredibly difficult for British people to appreciate the reality and scale of the tar sands project: a psychological set-point exists thanks to a false mythology that paints Canada as a clean, green nation of eco-minded liberals – a land of rivers, forests, wolves and hippies. Canada may have been awarded the Colossal Fossil award yet again this year, but China and its famous construction of two coal-fired plants a week still has a more predominant place in people’s minds.

This mythology of ecological enlightenment still persists among Canadians themselves. But self-identity and patriotism aside, most Canadians are certainly aware of the scale of the tar sand operations because it plays such a predominant role in the country’s economy and has such a highly visible presence in the mainstream media.

But even for those concerned about the impacts of the project – even for those saddened and angered by it – the sheer size of the operations is almost impossible to comprehend. Nothing like it has ever existed. It is without any historical precedent. It is, simply put, overwhelming.

One could watch documentaries such as H2Oil and Petropolis over and over or scroll through aerial shots for hours on end (which I have), and still feel like one has no appreciation of the true scale of the operation – not simply its size, but also the causes, the effects, and its future.

Confronted with the unprecedented scope of the tar sands, most people’s minds simply switch off. It’s too big, too overwhelming, and – frankly – too depressing for most Canadians to think about.

And without psychological inspiration, nobody is motivated to take action.

There are political and legal means to challenge the tar sand operations – most of all, the treaty rights of the First Nations communities, as Thomas-Muller argues. “Not a single environmental victory in Canada in 30 years took place without the enforcement of the treaty rights of First Nations,” he said. But the psychological barriers continue to prevent most Canadians from being inspired to act.

However, as Deranger pointed out, the responsibility for the existence of the sands – and the ability to oppose them – lies not just with Canadians. Financial institutions and petrochemical companies the world over are invested in the sands. British tax payers, no matter whom they bank with, fuel the sands through nationalized banks such as the Royal Bank of Scotland.

But moreover, purchasing the petroleum-derived products – which include polymer plastics, food grown with chemical fertilizers and pharmaceuticals as well as gasoline – manufactured by companies such as Shell, BP and other energy giants directly fuels projects in the sands.

“We are all contributing to this project because we are addicted to oil – because we don’t know how to move forward to renewable energies,” she pointed out.

Understanding that we each and everyone of us the world over play a small indirect part in the tar sands and the destruction of Alberta’s forests – and communities – through the complex carbon chains in our economy is even more staggeringly difficult to comprehend than merely the size of the project.

But until we are capable of appreciating this we will not move to oppose expansions in the tar sands – nor of making changes to our lifestyles and economy that underpin all of this.