Yesterday’s line: “Don’t do drugs, kids.”

Today’s line: “Kids don’t do drugs.”

A variety of publications have patted Millennials on the back with praising headlines, from The Economist’s “Millennials are less keen than previous generations on illicit drugs” to The Guardian’s “Sober is the new drunk: why millennials are ditching bar crawls for juice crawls,” and Now Magazine’s “These millennials are ditching booze to go sober — here’s why.”

The narrative: Millennials (typically defined as those born between 1983 and 2002) are less keen to get hammered, high, or horizontal compared to previous generations. Disillusioned with the hippies in the ’70s who went crazy (or at the very least got lazy and boring) from psychedelics, punks in the ’80s who overdosed on heroin, and ravers in the ’90s prematurely withered from speed and MDMA, these days, teens and 20-somethings have opted to take things down a notch.

It’s a nice idea: Today’s youth will not repeat the mistakes of their progenitors. Nobody likes seeing their friends die young from liver disease or lung cancer or lost to the hinterlands of the mind. I myself have lost a few.

But is it true? Are teens and 20-somethings really taking it easy or going sober? And if they truly are taking it easy on the chemicals, could it be for reasons that are actually unhealthy?

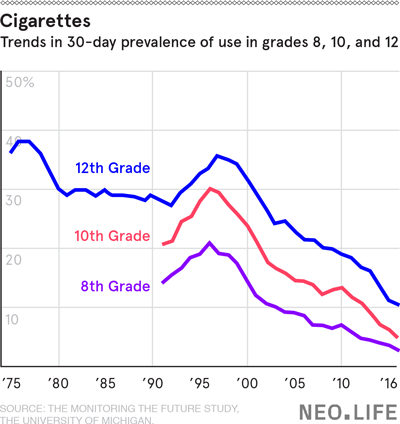

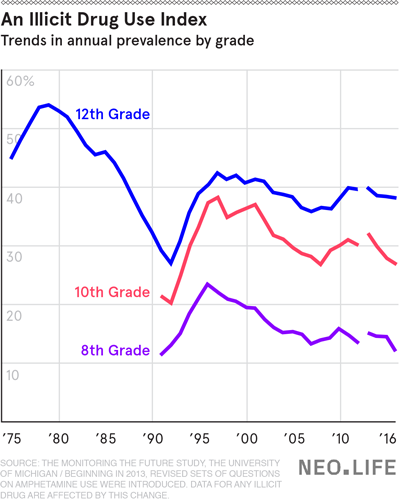

Richard Miech, a sociologist at the University of Michigan and leader of a National Institute for Drug Abuse-funded project called Monitoring the Future, says — based purely on the numbers, gathered from more than 40,000 8th, 10th, and 12th graders annually since 1972 — that yes, illicit drug use is on the decline. “Look at cigarettes and alcohol — the substances that were traditionally most commonly used. Millennials have very little levels of use compared to other cohorts,” he says.

Even where I live, in the United Kingdom — nicknamed “Booze Britain” by its own citizens — a report from the Office for National Statistics states that people 16 to 24 years old “are less likely to drink than any other age group.”

While marijuana is being legalized or decriminalized across the US, Canada, and Europe — usage is “stabilizing,” says Silvia Martins, associate professor of epidemiology of Columbia University, who has published more than 130 academic studies on substance use.

Overall, the trend toward less dabbling in drugs and alcohol among millennials “is definitely real,” Martins says. Nonetheless, pediatrician Sion Kim Harris, co-director of the Boston Children’s Hospital Center for Adolescent Substance Abuse Research, offers a caveat. Although teenagers appear to be getting wasted less often, Harris cautions that many of them are just making up for it in their 20s. “We are certainly seeing declines in substance use in those under 18 — but in the 18 to 25 group, those rates are not going down. If anything, they are going up,” Harris says. “The college environment is still very wet.” (Read: boozy.)

But if today’s teens really are more likely to lay off the hooch, cigs, and drugs, the ultimate question is: Why? Nobody knows yet. “I don’t know of any paper that has been published yet on the actual reason for this, because it’s just such a new phenomenon — it’s only been trending for a few years,” says Harris.

However, there are some compelling hypotheses. And each one carries troubling implications.

One: Selfie Obsession

The story goes like this: Kids raised on a steady diet of social media now live in mortal fear of looking less than stellar on Facebook or Instagram. If you grow up with the Internet from the moment you can speak, it’s probably natural to think of your online identity as being intrinsically tied to your true identity. Based on what we can see online, there are certainly far more images of youngsters looking pristine, and far fewer pics of them that resemble the sweaty ravers and wide-eyed hippies of bygone eras.

This also feels like part of a shift in political identity: San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury kids in the ’60s took pride in reclaiming the word “freak,” turning it from an ostracizing put-down to a celebratory title. Ravers in the UK in the ’80s and ’90s threw blow-out illegal raves thousands strong, gorging on ecstasy in a riotous love-fest, which they saw as a communal, defiant response to Margaret Thatcher’s cynical statement that “there’s no such thing as society.” A decade later British “ladettes” saw being able to match the boys pint-for-pint as a badge of honor. In a sense, it was a feminist statement: Whatever you can do, we can do just as well (or better), including boozing; let “lady-like” temperance become an outdated relic. Today, it’s hard to find a scene for the young so raucous — or so fun. Kids today just don’t seem to find the same rebellious joy in being altered in public.

Two: Academic Pressure

It’s fairly clear that the children of affluent families today have far greater workloads piled on them than in the ’60s or the ’80s. Now that a bachelor’s degree no longer guarantees an actual job, you’d better plan for further education. In this education arms race, where is there time to get high (and recover)? That would also explain the relative popularity of a concentration-enhancing drug like Adderall, a pharmaceutical that is utilitarian rather than euphoria-inducing.

Three: Depression and Anxiety

Even while there seems to be more pressure on youth now to excel academically, they’re also expected to appear happy and healthy. That would explain that while they may be drinking less, smoking less, and taking fewer psychedelics and stimulants. A study from Drugabuse.com (a substance and addiction information resource owned by Bloomberg LP) states that “prescription painkiller abuse is more common among millennials than any generation before.” That means kids are still using drugs; they’re just using them to numb pain rather than have fun. Research from Canada and documented in the Toronto Star describes demands for mental health services for university students as “exploding,” exacerbated by a dearth of funds and awareness. “There is a perception that this age group is healthy,” the president of the Ontario University and College Health Association told the newspaper, “but they’re not.”

Four: Technology Addiction

A variety of brain-imaging studies have suggested that people addicted to self-destructive habits of a non-chemical nature — such as gambling, video games, porn, shopping, or the Internet itself — get the same “hit” of the rewarding neurotransmitter dopamine that biological treats such as drugs, sex, and sugar provide. Evidence for this “dopamine hit” remains inconclusive, but there has been a clear rise in the use of interactive technologies in teens alongside an apparent decrease in illegal drug use. Mark Griffiths of Nottingham Trent University studies how “screenagers” and “digital natives” over the past two decades have increasingly spent time playing video games and jabbing smartphones while at the same time committing fewer crimes (such as being arrested for drug offenses). “It makes pure sense that if you spend eight hours a day in front of a screen, that detracts from your time spent out being able to buy drugs,” he says.

Five: Cocooning

Most of us — from children to adolescents to parents and grandparents — now can spend most of our time at home, doing nearly everything that once brought us into the wider world: grocery shopping, watching movies, communicating with friends, and so on. If teens don’t need to leave the house to interact with friends, surely there will be fewer opportunities to run into the neighborhood bad boys? To cap that off, parents are less keen to tell their kids to “go outside and play” after the 1990s panic over child abduction.

I have my own hypothesis, which I shall entitle:

Six: The Drugs Change, the Song Stays the Same

Although drug use is lower than it was in, say, the 1970s, the Monitoring the Future study shows an eyebrow-raising pattern: From 1995 to 2016, levels of usage by American 12th graders stayed pretty steady. In other words, kids have been doing the same volume of drugs. But they are doing different drugs. They may smoke less and drink less — which are both indisputably good trends. Instead they are taking more pharmaceutical sedatives—as noted, prescription painkillers and opiates seem to be the Millennial drugs of choice.

A big question then presents itself. If the five hypotheses that academics have suggested (selfie obsession, academic pressures, depression and anxiety, technology addiction, cocooning) are all accurate, then is the fact that kids are indulging less in fun drugs and more in sedating drugs really such a good thing?

I also can’t help but wonder: What about the influence on their creativity and on popular culture? Whether it was the psychedelic explosion of the ’60s and ’70s, or the stimulants and pills of the ’80s and ’90s, it’s undeniable that some of the most interesting art, music, novels, and films of the 20th century were forged through experimentation and intoxication. Without art made by sublime wreckheads, our world will be poorer for it. I for one don’t want to be subjected to an explosion in Xanax-inspired novels.

One last thing: what do teens and 20-somethings themselves have to say about all the academic pontificating on their drug-taking habits? I interviewed half a dozen Britons ranging from 17 to 25 years old, and most of them had the same thing to say: They actually still do the hard drugs like ketamine, cocaine, MDMA, and so on. They’re just better at hiding it.

“Obviously I don’t know that much about previous generations,” says Bella Brown, 18. “But if you look at the ’60s, ’70s, ’90s, a lot of the pictures taken almost seem to be advertising drug use. Now it’s more on the down low.Everyone is more conscious about impacts on your future career.”