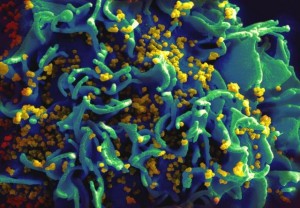

It’s the holy grail for scientists working in sexual health: a device that women can use discreetly to protect themselves from contracting HIV.

Worldwide, only five percent of men wear condoms routinely. Convincing men to wear them can be difficult to say the least, especially in regions where rape is at epidemic levels. Dumping millions of condoms onto developing countries every year has not changed the fact that one in five people in some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa have HIV.

The International Partnership on Microbicides (IPM) hopes that the “Dapivirine Ring” could be the solution we have been waiting for. A non-profit, the IPM has managed to secure funding from a broad range of philanthropic and national organisations, because the need for a female-controlled form of HIV protection is so desperately needed.

“We’re hoping that, for the first time, an anti-HIV ring will help women be able to protect themselves against infection,” said Zeda Rosenberg, chief executive officer of IPM.

The Dapivirine ring is a porous silicone hoop designed for women to wear around their cervix. It is soaked in an anti-retroviral drug capable of killing the HIV virus, which is slowly released over time; women will need to change the ring monthly. Because they carry it with them day-in-day-out, even if condoms aren’t to hand, women will be able to know they are protected—especially important as women are twice as likely to be infected with HIV through sex with a man than vice versa.

The Dapivirine ring is currently being tested in Africa in Phase III clinical trials, involving thousands of women. More than 5,000 women worldwide have tested the ring so far. These foot soldiers on the frontlines of the war on HIV are taking the brave step of road-testing an experimental device, knowing there’s a chance they could still contract the virus (they are also given male condoms). Will it work? Preliminary results are expected in 2016, and it could be available in target countries in Africa and the tropics by 2018.

The Dapivirine ring is just one of many microbicide rings being developed worldwide in the race to create a discreet barrier protecting women against HIV infection. Virginia-based CONRAD—which has been in the field refining protection for women for two decades—is developing another front-runner.

This is not the first time that “female-controlled” microbicides have been hailed as poised to change the world. Last time, it was a catastrophic disappointment. In 2004, scientists believed we would have microbial gels on the market by 2010; more than 60different kinds were being tested, in the form of gels, sponges, creams, suppositories, and rings. But clinical trials revealed that not only were many ineffective, some actually worsened HIV infection rates: cellulose sulphate vaginal gels, for example, were slightly caustic to the vaginal tissue and increased the risk of tiny tears that make infection more likely.

“The failure of the gels in the 2000s was very disheartening,” said Rosenberg. But the need for an effective microbicide is so urgent, IPM, CONRAD and other organisations felt abandoning the goal would be unconscionable. Rosenberg has been working in the field since the 90s and remembers the hype, the hope and the disappointment of microbial gels very well.

Considering that it might be impossible to create an HIV vaccine, IPM—which has been working for 11 years on this concept—thinks their antiretroviral (ARV) drug-soaked rings could be the horse to bet on in the battle to halt the pandemic. The rings are intended only for release in the developing world, because that is where they are most needed—essentially flipping the traditional R&D model on its head by creating something explicitly for the developing world first, rather than rich countries.

Crucially, their work has been funded by philanthropists, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has gifted them with grants of up to $130 million. Much like the development of the combined progesterone-estrogen pill, bankrolled in the 1920s by philanthropists and suffragettes Margaret Sanger and Katharine Dexter McCormick, who felt that the world needed a safe contraceptive women could control, microbicides have been fueled by political conviction.

“Despite the failures of microbicide gels, there’s still a lot of interest in rings because they are—in terms of contraception—relatively low dose, and the Nuvaring [a contraceptive ring already on the market] is pretty popular,” said Terri Walsh, director of research and evaluation with the California Family Health Council (CHFC) in Los Angeles. Eventually, the plan is to produce a ring that prevents both pregnancy and HIV infection. “The possibility of having a ring that contains a microbicide and a contraceptive, in the same device? Now that would very attractive.”

But just because an idea sounds amazing on paper doesn’t mean it will actually work in the sweaty, messy, real-life scenario of the bedroom. Take the female condom, which sexual health specialists have long championed as a “female-controlled” prophylactic that gives women the power to protect themselves even if an inconsiderate lover refuses to don a condom. Whether or not this is actually true remains unclear. Surely a man can refuse to penetrate a female condom just as easily as refuse to wear a male condom—or (in the case of rape) yank it out?

More importantly, the female condom routinely ranks just a 16 percent approval rating in clinical trials. As the husband in one LA couple told me when I was researching for a piece on new designs in condoms, “They are terrible and deserve their reputation.”

Will women find inserting the ring cumbersome or wearing it unpleasant?

“We didn’t have any trouble with our participants putting in the Dapivirine ring,” said Walsh of the CHFC, who conducts trials to test new forms of contraception (such as their large-scale condom “breakage and slippage” studies). Considering that Nuvaring is already on the market with fair success, it’s reasonable to assume that HIV-preventing rings should be equally unobtrusive.

How’s the study going? “Everyone is holding their breath,” said Rosenberg. “And at the end of the day, we have to remember that these viruses mutate and adapt quickly, so we will still need to keep on our toes and simply not assume that everything has been solved when one product comes out.”

In other words: even if the Dapivirine ring proves successful, it won’t be the last weapon we will need in the fight to protect people—and women in particular—from HIV.

“Just as we have a variety of birth control options that women can use at their discretion—pills, rings, IUDs, diaphragms, injectables, implants etc—we need to keep in mind that women also need a variety of options when it comes to HIV prevention, because we all have different needs,” said Annette Larkin of CONRAD, which hopes to have its microbicide rings in women’s hands (or, rather, around their cervixes) in the next three years. “Currently, there are no HIV prevention methods that women can use on-demand and at their discretion. Why would we NOT do this research is the question.”