It is not exactly your average venue. The concrete cobblestones were cold, spare couch cushions served as chairs, winter winds wafted into the room. Police sirens blared. There were tents everywhere. And, every hour, loud bells would gong in the cathedral towering overhead.

But the small cinema at the Occupy London Stock Exchange, at the foot of St Paul’s Cathedral, has been screening films since the inception of the sit-in over a month ago.

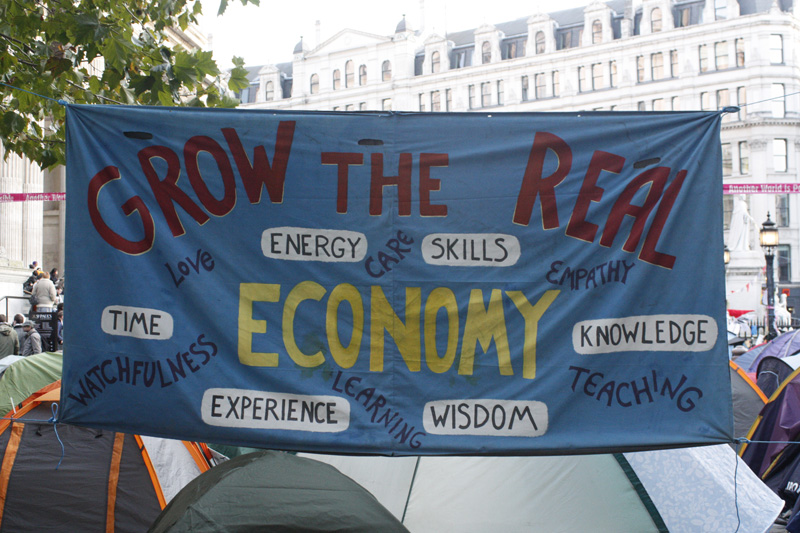

“There is a lot of talk about the financial crisis, but we have to ask: how were we so uncritical about what was going on? Finance has been able to dominate our lives in part because we have stopped imagining that other worlds are possible. Tent City University, and Occupy in general, is about creating an open, participatory space where these possibilities can be explored,” says Christopher Fraser, who runs the cinema at the camp.

But the British début of the new US documentary Growthbusters at the camp might seem puzzling, counterintuitive and even offensive to anti-poverty campaigners at the camp and the millions of people worldwide who have lost their homes and jobs, hard-hit by the fallout from the global recession.

When the economy is in free fall, who would be against growth? Intuitively, growth symbolizes health and prosperity – the London camp is itself growing, spread now to Finsbury Square and an abandoned UBS building – surely a sign of its resilience, and potential longevity.

Supporting growth seems like a universal point of agreement: British Prime Minister David Cameron’s pledge to kickstart the economy by building 450,000 new affordable homes for first-time buyers, announced this weekend, seems hard to argue with.

Affordable homes for new families, jobs for labourers, more income in their pockets to spill in the rest of the economy – what could be more sensible?

A generation of ecologists, demographers, and a few unorthodox economists, however, have together built the case that growth is not the solution – it is part of the problem, and a core component of an economic model that needs to be changed.

“We need to learn to embrace the end of growth, or go down fighting,” says Dave Gardner, the film’s director.

His words might seem hyperbolic, coming from the mouth of a filmmaker from Colorado who unsuccessfully runs for local government in his community on a platform opposed to more growth (he exposes the whole amusing saga, including uncomfortable and cantankerous moments at City Hall, in the film). But to those familiar with the subject, it is notable that Gardner bagged interviews with all the heavyweight thinkers in this field, whose arguments are woven into the film to support his case.

The hitlist: Canadian scientist Professor William Rees, the very founder of the concept of the ‘ecological footprint’ who made popular the notion of the earth’s “carrying capacity” (which, by the way, we are already overshooting by 30 per cent); retired economist Paul Ehrlich, author of the Population Bomb, who first raised the alarm over human expansion back in 1968; Herman Daly, a former economist with the World Bank; Bill McKibben of 350.org; Raj Patel, author of Stuffed and Starved; the list continues.

Essentially, they all argue that we need to de-link the connection in our economic and financial system between prosperity and the GDP growth, and achieve a sustainable economy (also called a ‘steady state’ system). But though the idea has been bandied about for decades, the system remains unchanged.

“There are individuals and companies who profit from growth – it is in their interest to keep us hooked on growth,” says Gardner. “These ‘growth-pushers’ [financial institutions, energy companies, and so on] profit, while society and future generations pay. They make easy short-term profits, dependent on us encouraging and even subsidizing them to plunder our communities.”

The term “subsidize” might jump out at most readers, having watched the banks deemed ‘too big to fail’ propped up with public funds.

“Documentaries can be an important source of evidence in challenging conventions, and Growthbusters is a fantastic example of this,” says Fraser. “The ‘growth-pushers’ it talks of help perpetuate the idea that growth will deliver prosperity. But perhaps the core myth of our time is that deliberation of these matters is pointless – or best left to experts. Neither is true.”