I expected to smell better than two boys who had not washed for 40 days.

I did not expect to be deemed less attractive than an orangutan.

“You will never live this down,” my best friend grinned.

The things we do for science.

At the Feast of Stenches at the Secret Garden Party this past July, we presented our audience with an array of human scents for them to sample, judge and rate: two boys, a woman (myself), and an ape (Hannah, a female orangutan, only revealed to be non-human after the judging).

More than 50 eager noses took turns sniffing our Smell Stations, plastic boxes containing ripped shreds of fabric from t-shirts worn by our four research subjects.

This was a Guerilla Science take on the famous t-shirt experiments, which investigate the molecular basis of attraction and by examining how humans preferentially rate the smells of other people.

“We humans usually think that we pick our mates according to how they look – we think of ‘love at first sight’ – we don’t appreciate the importance of smell,” says Dr Leslie Knapp, an immunogeneticist at the University of Cambridge and a global authority on the relationship between smell and attraction in primates. “But studies of primates and even studies of humans have shown that our ability to smell is very important, even in present day society – how we perceive the smell of someone has an influence on how we react to them, and there is good evidence to suggest that it has important influences on how we choose our mates.”

Anyone who has ever known the smell of a lover may be able to relate: the scent of that certain someone is utterly distinct, wholly individual, and – when it belongs to the right person – completely intoxicating. Once upon a time, it was the smell of someone that lay in the crease between his nose and his face that made me weak in the knees.

The mysterious charm and allure of a particular person’s scent is seemingly impossible to put into words, though a few have uttered some rather poignant phrases: Napoleon is reputed to have written to Josephine, “Will return to Paris tomorrow evening. Don’t wash.”

Canadian gay gospel outfit The Hidden Cameras croon in The Smell of Happiness, from the album The Smell Of Our Own, “Happiness has a smell I inhale… I feed my own face when I soon crave a taste of the neck of a boy.” The rest, um, gets a bit dirty – read full lyrics here.

The influence of smell over our hearts and our bodies is undeniable, if you have ever felt that way, and yet exactly why seems mysterious: why should one person smell so sweet?

Scientific research, wielding the modern tools of genetic analysis, has uncovered some fascinating clues. Remarkably, studies have shown that our preferences for smells are partly determined by subconscious genetic cues. The same genes that determine how we smell – known as the “MHC cluster” in animals and the “HLA” in humans – also play a key role in programming how our immune systems operate by determining what innate and individual resiliences we all possess.

Lab animals as well as people will preferentially chose mates who possess MHC clusters that are different from their own, which most scientists believe acts as a subconscious mechanism that protects against inbreeding, as well as confers a greater spread of protection to their children.

Dr Knapp’s own research on mandrills has demonstrated that individuals will use smell to “identify potential partners with the appropriate genes,” as she puts it.

In humans, some fascinating studies (such as this one) have found that when women are shown photographs of men and given a selection of smell samples from the same men (though without knowing which smell belonged to which man), their choices frequently matched: the scents they deemed sexy often came from faces they declared handsome. Remarkable.

In the spirit of renegade research, we decided to conduct our own investigation into the relationship between smell and attraction, asking our audience to judge the smells of our contestants with a Feast of Stenches at the Secret Garden Party, sponsored by the Wellcome Trust as part of their Dirt season of events.

We gave things a twist, as we are wont to do. We threw a non-human – the orangutan Hannah – into the mix, without telling our unwitting judges.

To thicken the plot (or at least, their odours), we had our two male subjects go without washing for forty days and forty nights in the run-up to the festival, in a Smelly Tweeter competition.

For the chance to win a ticket to the Secret Garden Party, we asked contestants to attempt to last 40 days without soap and water, and tweet daily about their experience of being physically filthy, the reactions of those around them to their odiferous state, how being dirty makes them feel, and their reasons to quit the contest should they choose to drop out.

You can see all the tweets from contestants on Twitter under the hashtag #smellytweet. Daniel, the champion, kept a detailed blog on his experiences – you can see a choice selection of his posts here: “I am sitting less than three metres from a bathtub. This is torture. I will persevere. I WILL persevere.”

Beyond having a good chuckle at their expense, we hoped to enrich our understanding of the cultural implications of dirt: “This will be something that no-one has ever done before – this is a totally unique experiment,” says Dr Knapp. “Humans usually try to cover up their natural odours, so we will be interested in the results.”

The audience’s first task was to guess the gender of each of the four stations using coloured beads to indicate male (blue) or female (pink). The overwhelming majority vote in every case was correct – most people could tell that Daniel and Jim are male, and Hannah and myself are female. (Somewhat humiliatingly, more people thought Hannah was female than thought I was female.)

Next we asked the audience to rate the four smells on a sliding scale of attractiveness. Daniel was deemed least attractive, Jim somewhat less so, followed by myself – and then Hannah, the orangutan, was declared the most pleasing. My friends said this would keep them in jokes for weeks to come (and that afternoon called their team in the pub quiz “ORANG-

UTAN > ZOE”), but I query this conclusion: Hannah’s shirt smelled more like laundry detergent than any of ours, presumably because she did not have the patience to wear it for long. Had she kept it on her hairy form for as long as I did, I believe I would have won. But I digress.

Our last table featured strips from four shirts, all worn by Daniel, at various points during his 40 day soap fast. Unsurprisingly, the shirts worn at the later stages were deemed unbearably putrid.

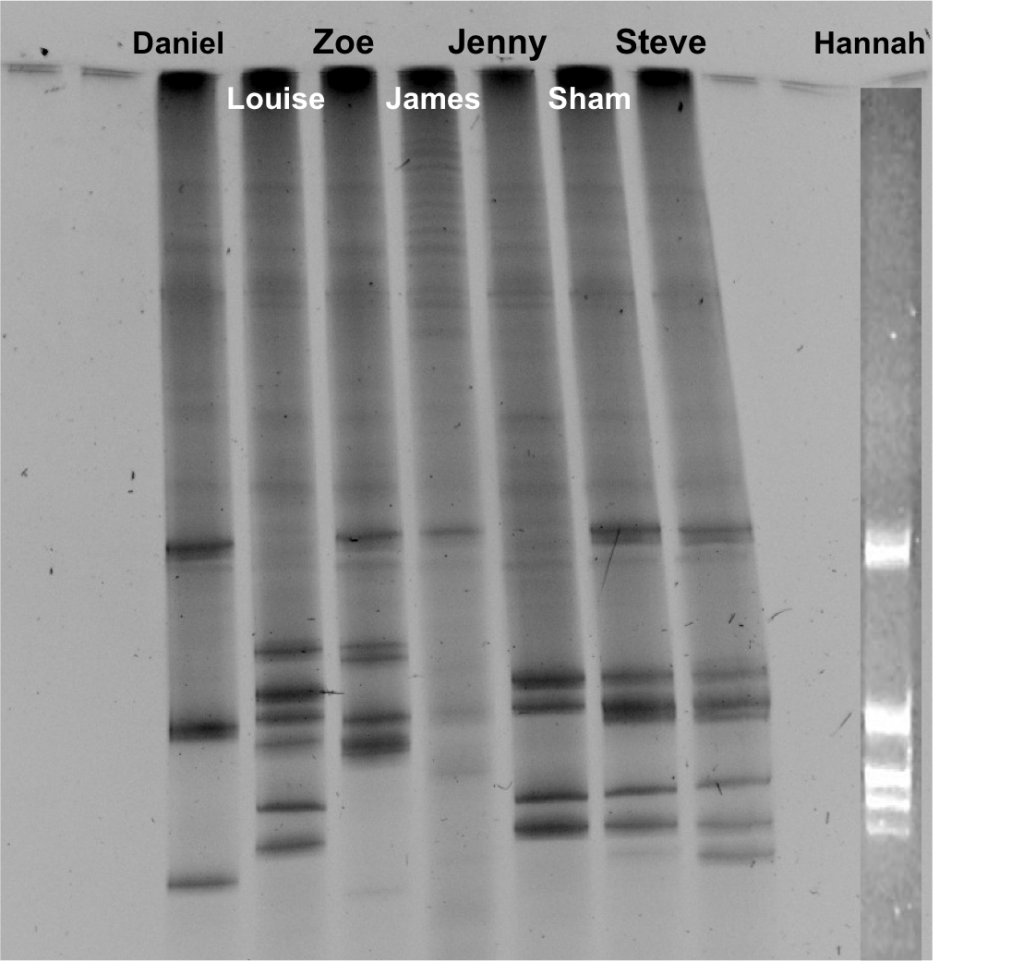

But here’s where things get more interesting: Dr Knapp examined our DNA, extracted from mouth cheekswabs, and produced visual illustrations (in the form of gel electrophoresis assays, which display genetic variations in the form of lines) of our HLA genes. She also examined the DNA of Shamima, Daniel’s long-term girlfriend.

Unsurprisingly, Sham (who descends from both European and Asian parents) boasted diverse HLA genetics – Daniel, who’s lineage is largely Irish, possessed more homogenous genes, which would make him less immunologically robust and more vulnerable than Sham.

But, amusingly, Sham deemed the smell of the other boy, Jim, to be more attractive than Daniel – and his genetics looked to be a better match for her as well, said Dr Knapp.

Of course, being social creatures who rely so much on language, and whose beliefs, desires and behaviours are largely governed by the cultures in which we live, we use far more than just smell to pick our partners. It certainly makes life more interesting.

But the results are certainly fascinating, nonetheless. And even if Hannah was deemed more attractive than me, I do take pride in having defeated the boys – even if they hadn’t bathed in 40 days.