Canada sparked headlines around the world this winter by making its national anthem “gender neutral”, modifying the lyrics to give equal recognition to all sexes.

The nation’s athletes mumbled their way through the new version at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang as the country racked up 29 medals.

“Canadian women play major roles in all spheres of society, and their contributions should be reflected in one of Canada’s most cherished national symbols, the anthem,” says Dominique Tessier, spokesperson for the Ministry for Canadian Heritage.

Not all harmonious

The proposed change, however, was met with fierce opposition by those who described it as an affront to the nation’s heritage. Liberal Senator Joan Fraser criticised the change as “clunky, leaden and pedestrian” while Conservative Senator Michael MacDonald denounced the need for a “social justice warrior seal of approval” as “political correctness”.

“If we are constantly revising everything because it was written in another generation, our national symbols will have no value. Our history means nothing in this country anymore, and it’s a shame that we’re doing this.” he said.

Yet, for all the vitriol, the alteration is minuscule: just two words. “True patriot love in all thy sons command” will now be sung as “True patriot love in all of us command.”

But the edit was seen as a victory in the eyes of supporters, particularly in the wake of the #MeToo movement, which saw thousands of protesters on the streets in cities such as Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa. Women, trans-gender, and people of every conceivable identity will be officially recognised when the anthem is sung by primary school students, athletes, and soldiers deployed overseas.

Canada follows in the footsteps of Austria, which changed its anthem in 2012, and other countries such as Germany and Peru now toying with the idea.

Two words. But at what price? With new textbooks, immigration brochures and citizenship certificates to be printed, what are the hidden costs?

The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is nothing. Zero, zip, zilch.

It has not cost the public purse a single dollar.

This prudence is interesting and in sharp contrast to other costly moves to change national symbols. A failed 2016 campaign to change the New Zealand flag, for instance, cost taxpayers millions of dollars.

After the votes the NZ Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet released a breakdown of costs of two flag referendums, which showed it cost NZ$21.8m or US$15.3m. The first postal referendum cost NZ$9m (US$6.32m) alone, while the fees and travel of the 12 members of the Flag Consideration Panel cost NZ$284,000 (US$199,291).

Changing currencies can also be an expensive process. The Bank of England redesigns its notes every 20 years and the fifth redesign of the £10 note introduced in 2017 now features writer Jane Austen. But if Prince Charles becomes king, notes and coins will immediately go into production bearing the new monarch’s portrait.

So, perhaps it is fair to consider that the wider perception must have been that this change risked becoming very pricey? And after all, the Canadian government has form here – removing old insignia and weaving gold braid, “pips” and crowns back onto naval and military uniforms cost more than CDN$4.5 m (US$3.5m).

“When I took over sponsorship of the bill in the senate, the possible costs were something I checked frequently with the Ministry for Canadian Heritage,” says Senator Frances Lankin. “From the very beginning, we were told there would be no extra cost.”

“The change to the lyrics will be introduced as part of the normal refreshing or reprinting of materials – if and when needed – so there will be no additional costs,” says Tessier.

The ministry has an ongoing budget for a variety of printed materials related to the federation, she explains, and they simply reprint from time-to-time when new supplies are needed. Updated versions, which would be produced regardless, will simply have new lyrics – using only as much ink as when they were first published. It was decided that publicity campaigns to advertise the change would be unnecessary: the new lyrics will spread through media coverage and word-of-mouth.

“This is already happening – and it’s been happening for decades. I’ve been singing the different lyrics myself for 25 years, as have various women’s groups and choirs across the country,” says Lankin.

Bill C-210, passed by Parliament in June 2016, was just one of 12 bills that had already been tabled over the last four decades.

“So, this really was just a piece of unfinished business,” says Nancy Ruth, a feminist and a ‘red Tory’ or “fiscally conservative but socially concerned” as she puts it – who served in the Canadian Senate from 2005 to 2017.

“We figured we should still give it a kick of the can,” says Ruth. “Obviously it’s nothing compared to tackling violence against women, or equal pay, but it was something needed to be done. We had women coming back from Afghanistan in body bags and the anthem being sung did not recognise their sacrifice.”

Leading Canadian feminist, Elizabeth Renzetti, columnist for Canada’s largest national newspaper The Globe & Mail and author of Shrewed: A Wry And Closely Observed Look at the Lives of Women & Girls, is equally withering,

“Our anthem is sung only a few times a year – the Olympics, the Stanley cup, and that’s pretty much it. My own kids don’t even know the words to ‘O Canada’ – they only hear an instrumental version every morning. But in this instance it became a cultural flash point.”

If it cost nothing, why such a fuss?

“They were just using it as a way to inflame cultural divisions,” she says. “Part of the problem was the phrase ‘gender neutral’. If they had simply described the lyric change as ‘fair’ or ‘modern’ people wouldn’t have gotten their backs up. There is still so much sexism in our society, every time you mention gender equality men think something is being taken from them.”

“The lyrics to ‘O Canada’ have never been constant: in 1967 a committee found 45 different versions of the lyrics being sung across the country,” laughs Renzetti. “There has never been stability in the language.”

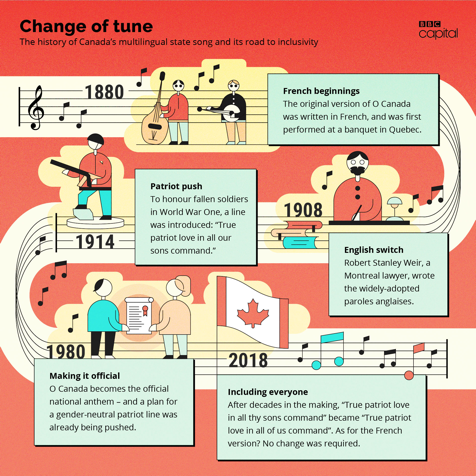

In fact, the contested line “in all thy sons command” itself was a modification of a phrase that was gender neutral in the first place. When Robert Stanley Weir penned the English lyrics to O Canada in 1908, he composed: “True patriot love thou dost in us command”. Those words were changed in 1914 to honour the men and boys fighting in World War One.

“Canadians tended to think that the English version we sang before this bill for gender neutrality had never changed – so that made them very nervous,” says Beth Atcheson, a lawyer who served as Director of Parliamentary Affairs for Ruth. “Opponents complained the anthem was untouchable because it was a memorial to the men who had died in WW1. But I think it was controversial because it touched on issues of sex and gender.”

“Inclusion remains controversial, and there is not a single form of equality that women haven’t had to fight for,” says Atcheson. “The anthem is owned by all the people of Canada. So, the question is: Who deserves to be acknowledged? Who owns our history?”

Most of the bills were tabled by men who cared passionately about getting the song changed. The most recent and final bill was sponsored as a Private Members Bill by the late Liberal MP Mauril Bélanger (1955 – 2016). By the time his bill reached a second reading in Parliament, Bélanger was in hospital, slowly dying from ALS (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as motor neurone disease).

His wife Catherine helped him get to Parliament in an ambulance with medical staff so he could vote on the bill. “It would have died without his vote – and we took him in an ambulance again at the third reading, when he was in the final stages at home.”

MP Bélanger died two months after Parliament passed the bill – but it took another 18 months for the Senate to pass it.

“The conservatives tried everything to stop it – the most ridiculous, childish, unusual tactics – it was almost a miracle to get it to the vote,” says Catherine Bélanger. “They wrapped it up as a matter of tradition – which is exactly what happened when they tried to change the flag in the 1960s.”

Her husband didn’t live to see the final result – but even so, Catherine says she is on “cloud nine” that the new generation of young girls will grow up feeling included. “Seeing the outpouring of emotion from women has been so rewarding. It’s definitely been an interesting journey.”

“It’s a tiny change, but it’s significant” says Sarah Barmak, Toronto author of Closer: Notes on the Orgasmic Frontier of Female Sexuality. “This will affect the newest generation of Canadians most, because kids are the ones singing the anthem regularly in school. The old anthem sounded truly archaic – it placed boys and men first as citizens.”