Every day, around 80-90% of adults and children consume caffeine in one form or another – in coffee, tea, fizzy drinks, chocolate and more. Not only is it ubiquitous – truly the world’s most popular drug – it’s spectacularly habit-forming: a morning without coffee can feel like existing in the hinterlands of awareness, groggy shufling at our desks nothing more than time ill-spent.

Although there are many definitions of addiction, truly addictive substances are not only habit-forming but produce physical withdrawal symptoms when users quit. Caffeine certainly seems to fit this category: the worst physical ache I’ve ever experienced owing to a drug occurred the day I attempted to go cold turkey from caffeine. The headache was unbearable and only alleviated by a desperate dose of coffee (both water and paracetamol proving ineffective).

ADDICTIVE SUBSTANCE?

Modern academic opinions on the meaning of addiction vary and there’s much hair-splitting, but yardsticks include a chemical’s capacity to produce dependence (an insatiable need for a substance), tolerance (long-term use results in the capacity to consume ever larger amounts) and reinforcement (the more you take it, the more you want it). Caffeine meets all these criteria.

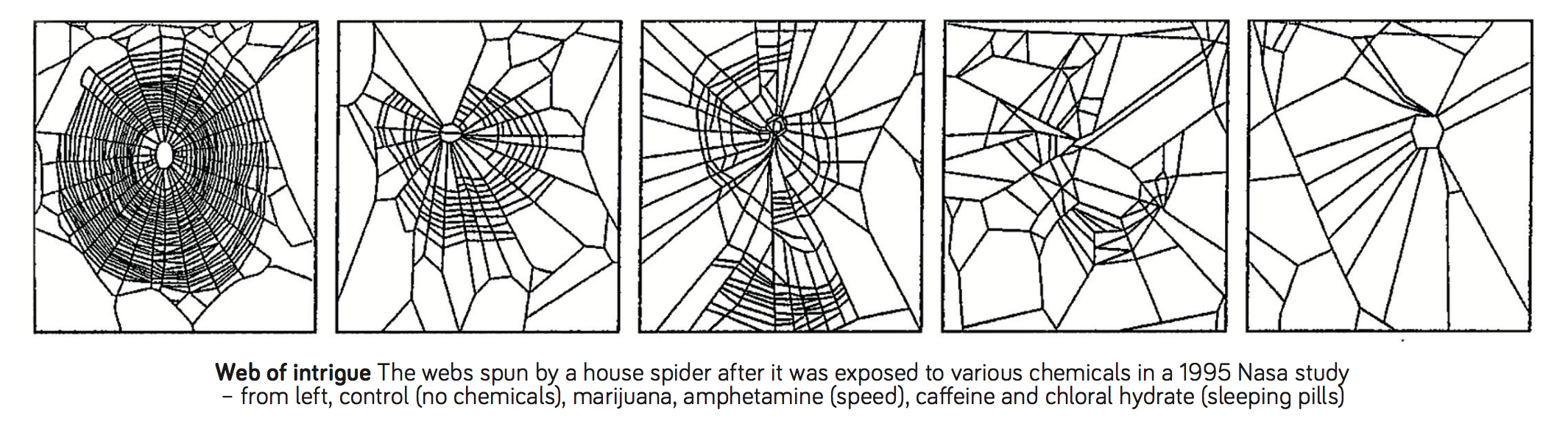

But just because caffeine is addictive, does that mean it’s harmful? In the 1940s, experiments by Swiss pharmacologist Peter Witt found that different drugs had various alarming effects on a spider’s ability to spin a web. In 1995, Nasa repeating the experiments with speed, marijuana, chloral hydrate and caffeine, the latter resulting in the most mangled web (see p32), hinting at toxic neurological effects.

Modern psychiatric analyses have also led to finger wagging from the highest authorities in psychiatry. The 2013 edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic & Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders– often referred to as the “bible of psychiatry” – lists caffeine withdrawal as an official condition for diagnosis. Symptoms include the usual suspects: fatigue, headache, difficulty focusing, irritability and cognitive impairment, plus the flu-like symptoms that characterise withdrawal, such as nausea, muscle aches, fever, sweats and shakes.

This may sound extreme, but a report from Johns Hopkins University’s behavioural pharmacology research unit in 2003 described 11 people

who met the criteria for “caffeine dependence”. They experienced far more extreme reactions when forced off java, including mistakes on the

job, missed days from work and screaming at their children. One poor coffee drinker even had to cancel his son’s birthday party because he was so impaired. The scientists involved went on to study further addiction to the world’s most popular drug, and in 2013 argued in the Journal Of Caffeine Research that “caffeine-use disorder” is a real medical condition that is not only widespread, but under-recognised.

MEMORY-BOOST

It may not all be bad news. The same institution released another study the very same year in the journal Nature Neuroscience claiming caffeine can improve your memory. “We were able to get an improvement in memory performance by about 10%,” says Dr Mike Yassa, one of the study’s lead authors. “In educational terms, a 10% boost in performance can make a big difference.”

While countless studies in the past had shown how caffeine improves performance in memory tests, the flaw in those studies was that the caffeine was administered before people learned the material and did the test, says Dr Yassa. This meant it was impossible to say if caffeine improved memory itself, or just test scores by increasing people’s levels of attention, awareness, vigilance and processing speed. In this study, people were given 200mg of caffeine – about two cups of coffee – five minutes after showing them a series of images. The next day, the people given caffeine outperformed those given a placebo in identifying certain images as similar but not identical to the ones seen the previous day. “So when it comes to memory, caffeine improves the sensitivity to detail,” says Dr Yassa. “It’s a very specific form of cognitive rescue.”

Dr Yassa and his colleagues are now studying the potential of using chemical relatives of caffeine as an intraventional treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. These chemicals will bind to the same adenosine receptors in a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which is crucial for memory formation, as caffeine but will avoid the jitters, impact on sleep and other annoying side effects of using the real deal.

A number of long-term, longitudinal studies of large numbers of people

have also suggested that daily coffee drinkers have a lower risk of developing dementia. In fact, the number of studies that have found some form of health benefit from coffee span a spectacularly reassuring range of effects.

HEALTH BENEFITS

People have long worried that coffee and the caffeine it contains can lead

to cardiovascular problems, which makes intuitive sense given its ability to increase your heart rate. But while some studies suggested this is the case, others have said otherwise (as is always the case with large-scale health surveys). In fact, a 2014 meta-analysis – a study of all the studies – from the Harvard School of Public Health looked at 36 papers, covering more than 1,270,000 people. Pooling all the data revealed not only did caffeine – and coffee speciFIcally – not lead to heart disease, but in fact had a protective effect: people who drank three to ve cups of coffee a day had a lower risk of heart problems. And even people who drank ve or more cups a day did not have an increased risk.

Looking at another health risk long thought to be worsened by coffee, stroke, a 2011 Swedish meta-analysis found not only did coffee not increase the risk of stroke, but consuming moderate amounts of it could have a mildly protective effect.

The list goes on. A study of studies of cancer risk found that drinking two cups a day of coffee led to a lower risk of developing liver cancer by 40%. And this year, a survey of more than 400,000 people in the US found that daily coffee drinking reduced the risk of liver cirrhosis – also by about 40%. In boozy London, fewer words from the stuffy annals of epidemiology could be more comforting. Meta-analyses have also shown coffee drinkers are at lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Coffee drinking has consistently been shown to be associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s, so much so that scientists in Canada are investigating how to use caffeine as a treatment for the neurological disease. Their 2012 study found, to everyone’s surprise, that caffeine dosing for people with Parkinson’s improved their motor skills, reducing tremors and shakes.

“If any other modifiable risk factor had these kind of positive associations across the board, the media would be all over it. We’d be pushing it on everyone,” Dr Aaron Carroll, professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, wrote in the New York Times. “For far too long, though, coffee has been considered a vice, not something that might be healthy.”

This points to an important truth: every single drug is a double-edged sword that can both harm and heal. Opiate drugs are severely addictive and occasionally fatal, but morphine is still the most powerful painkiller we have. Alcohol is toxic in countless ways, but studies have shown that in moderate doses it can have positive effects on stress reduction and may improve cardiovascular health. The list goes on. Yes, caffeine and coffee are addictive, but that doesn’t make them inherently bad.

Coming back to the potential for caffeine and coffee to prevent Alzheimer’s and improve learning, Dr Yassa’s study was in part based on the subtle work of Dr Geraldine Wright at the University of Newcastle. Her experiments using fake flowers full of sugar water showed that bees fed sugar water loaded with caffeine are more likely to stick their tongues out for more than those bees fed sugar alone. Through careful dissection of the bees’ brains after caffeine feeding, she also showed that caffeine triggers changes in the neurons linked with memory and smell recognition. Taken together, she thinks plants that lace their nectar with caffeine are training bees to remember their owers better, increasing pollination. More than 100 plants are known to do this.

“This was the first time a plant was shown to manipulate a pollinator by actively drugging them – that was very surprising,” says Dr Wright. Nectar is a food reward owers use to attract pollinators, but this is a whole other level of manipulation: narcotic seduction. “When you put this into the context of ecology, it is very surprising and very interesting.”

Humans are not bees, but mammals and insects share the same basic neural circuitry, so we can look to them to understand how our own brains work. And as studies into the effects of caffeine continue, it may yet hold many more tricks up its neurochemical sleeve.