If I asked you to imagine what evolutionary biologists have to say about human nature, the phrases “selfish gene”, “survival of the fittest” and “red in tooth and claw” might spring to mind. Perhaps you would imagine explanations for why human history is a catalogue of war, conquest and strife. We are greedy and violent, because the greediest and most violent ancestors triumphed. We must overcome our biology in order to coexist.

Not quite, says David Sloan-Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Biological sciences and anthropology at Binghamton University in New York state. “It’s impossible to explain society only in terms of self-interest, because we are undeniably a co-operative species,” he says. “We are the only primate super-organism.”

Throughout human history we can see co-operation as the driving force – in the formation of complex societies, in building monumental architecture, in industrial agriculture and in organized religion. Neuroscientists think that the cornerstones of the human mind – language, empathy, “theory of mind”, and perhaps even consciousness – evolved partly out of a need to function in large groups.

But the popular understanding of evolution is still dominated by two words: “selfish genes”, coined by the British biologist richard Dawkins, who attempted to explain all evolutionary change in terms of the survival of single genes. ‘What people don’t understand is that “selfish genes” doesn’t necessarily mean selfish individuals – our genes can cause us to co-operate,” stresses Sloan-Wilson.

It all comes down to the power of “group selection”, he argues: survival of the fittest groups, rather than the fittest individuals. Groups that are composed of co-operative individuals will always out-compete groups of selfish individuals.

Our undeniably co-operative nature also has a dark side. Without our co-operative roots we could never wage war, make nuclear weapons or commit genocide. “Some people think group selection proponents wear rose-tinted glasses – but the truth is nothing of the sort,” says Sloan Wilson.

This concept of group selection is as old as the theory of natural selection itself. Charles Darwin himself suggested the idea:

An advancement in the standard of morality will certainly give an immense advantage to one tribe over another. A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection.

Surprisingly, none of those famous phrases mentioned at the start of this piece can be attributed to Darwin, though most people would think those to be his words. “Red in tooth and claw” comes from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam A. H. H. “Survival of the fittest” – though later quoted by Darwin – was actually coined by Herbert Spencer.

Darwin, counter to the later “neo-Darwinists”, was fascinated by the prevalence of altruistic and co-operative behaviour throughout the animal kingdom and believed group selection could be a powerful force. There was widespread support for the idea until the 1950s, but individualistic and neoliberal ideas came to dominate many intellectual fields, from sociology to history, political science and of course, economics.

“The scientific story is embedded in the larger cultural story,” says Sloan-Wilson. “The ethos of the rugged individualist made it alluring to think we can explain everything in terms of self-interest.”

“Part of the problem is that Darwin struggled to explain the widespread phenomenon of co-operative behaviour because at the time there was no mathematical machinery to do that,” explains Martin Nowak, who teaches biology and mathematics at Harvard University.

Our own bodies are ecosystems

When scientists attempted to revive the idea of group selection in the 1960s, the concept was widely rejected.

Fellow biologist George C Williams flatly wrote in his 1966 tome, Adaptation and Natural Selection: “Group-related adaptations do not, in fact, exist.” Discussion over. The concept of group-selection became virtually taboo. Dawkins likened the search for evidence of group selection to efforts to create a perpetual motion machine in his 1982 book, The Extended Phenotype.

“For many years, Sloan Wilson stood alone defending the concept of group selection – and he turned out to be right,” says Martin Nowak.

In a highly cited paper published in the journal Science in 2006, Nowak used computer modeling, mathematics and rigorous experiments to identify five mechanisms that lead to co-operation, including group selection.

“Co-operation exists everywhere in nature,” asserts Nowak, from the flocking of birds to the giant hives of termites. And it can be a powerful force. Insect colonies such as those of bees, ants and termites, in which the members of a colony give up reproducing so a single queen can produce all the young, account for half of the total weight of all the insects on earth.

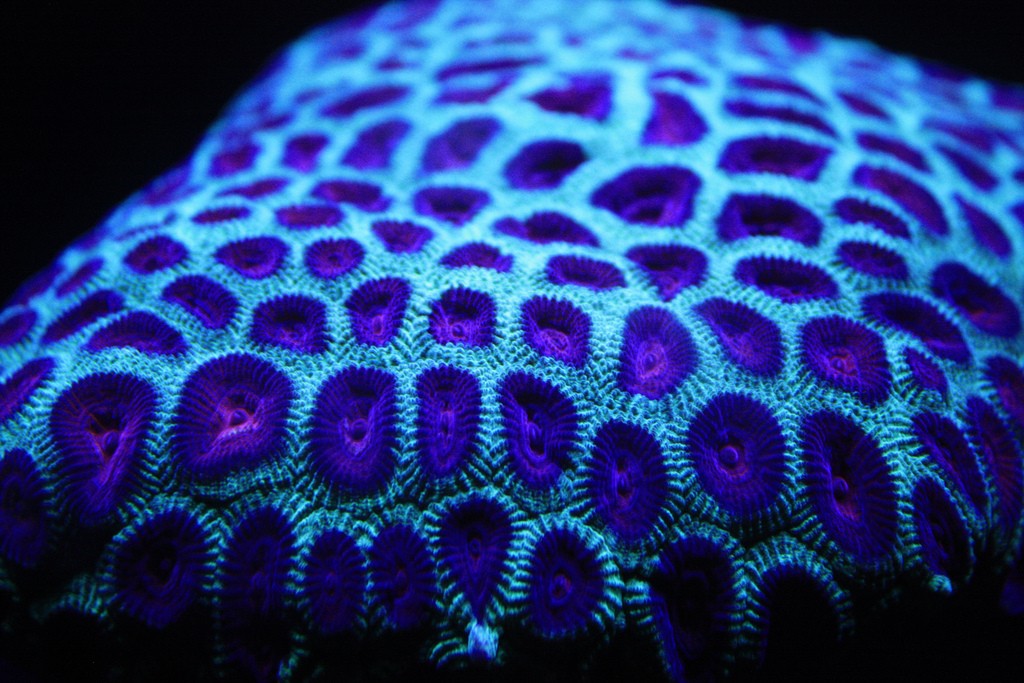

Co-operation between different species, not just between individuals of the same species, is of paramount importance to life in every corner of the planet. Plants depend on pollinators to reproduce; coral reefs rely on symbiotic algae to harvest sunlight; trees use networks of soil fungi to communicate. Our own bodies are ecosystems: for every one human cell we possess ten bacterial cells, many of which we are dependent upon for our survival, such as the germs in our guts.

In fact, many of life’s key innovations – going back three billion years – are simple forms of co-operation. The progression from single-celled organisms to multicellular entities is entirely reliant upon co-operation. Even the networking of chemicals was needed for the dawn of life.

As Sloan Wilson puts it: “Today’s individuals are yesterdays groups.”

The academic struggle for these ideas has rarely been easy. Scientists now believe that some structures inside our cells – mitochondria, the power houses of animal cells; or chloroplasts, the energy factories of plant cells – were once individual microbes which became co-opted by larger cells. But when the now famed biologist Lynn Margulis first proposed the “endosymbiotic” theory, “her ideas were considered heresy,” according to Steven Rose from Britain’s Open University.

“The controversy over co-operation arose particularly because of the extreme reductionism within which neo-Darwinism was formulated,” says Rose.

Those simplified explanations have penetrated deeply into popular consciousness. Sloan Wilson, Rose and Nowak all agree: everyone should be interested in this debate. Though theoretical biology can involve dense jargon and abstract mathematical equations, the basic concepts are not difficult.

“We don’t need big words to explain this – we all talk about altruism and selfishness all the time,” says Sloan Wilson. “Moral discourse by its nature is about the consequences of our actions as individuals and as groups.”

And the implications extend far beyond the philosophical. “The survival of intelligent life depends on whether we learn to co-operate with each other before we destroy the ecosystems of the planet,” argues Nowak.

“There is no technological solution. The solution requires a behavioural change.”

Meanwhile, Sloan Wilson has set up The Evolution Institute in his hometown of Binghamton, New York – an attempt to use biological science to influence society. “The idea that a thinktank could inform public policy from an evolutionary perspective is exciting,” he adds.

Rose is more sceptical: “Just because a group of wise scientists form a thinktank doesn’t mean we can solve all of society’s problems.”

That will take some time. And for now, “survival of the fittest” and “selfish genes” still reign in the public consciousness.

But at the very least, it’s worth reflecting on the etymology of the word “competition” which comes from the Latin compere, which means not “to defeat” – but “to strive together”.