In a darkened hall in London, a 20-metre high eulogy plays to a hushed crowd. A giant egg spans the floor to the ceiling. A mountain stands in a foggy sea, it’s peak towering over us. Red dots hover over the steps of an escalator. A snail slides across a pile of leaves.

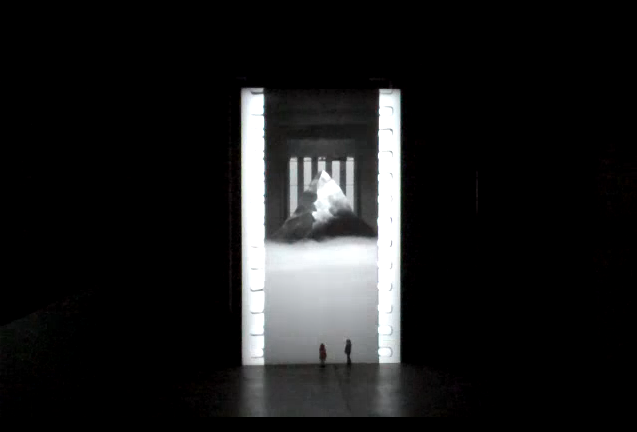

Suddenly, a child runs across the room, up to the screen, and pokes it. This is Film, a career-defining piece by artist Tacita Dean, which will flicker in silence on an 11-minute loop until the end of March, inside the great Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern gallery.

Since 2000, more than 26 million people have visited the gigantic showcase pieces of this hall, always with free admission. Invariably one of the UK’s most talked about annual exhibits, it takes centre stage at what is one of the world’s largest and most famous modern art galleries. Less than a dozen artists have been chosen to create a once-in-a-lifetime magnum opus here.

Often they’re spectacular: Rachel Whiteread, known for casting the interiors of buildings (such as her Holocaust Memorial in Vienna), filled the room with rabble dabble mountains of white boxes. Olafur Eliasson created an homage to the sun, using just a semi-circle of white fabric backed with orange neon lights, the entire ceiling lined with mirrors. Simple, but massively crowd-pleasing: visitors would lie on the floor basking in the sun’s warm light for hours, forming snowflakes with each other and watching their reflections on the ceiling.

Sometimes they’re more philosophical, or political: Columbian artist Doris Salcedo spanned the hall’s floor with a 160-metre long crack to, as the artist said, “represent borders, the experience of immigrants, the experience of segregation, the experience of racial hatred.” Outspoken Chinese dissident Al WeiWei (currently under investigation in China for “tax crimes” and more recently investigated for creating “pornographic” images) covered the floor with millions of hand-painted ceramic sunflower seeds, a metaphor and commentary on the turbo-charged industrialisation of the country and the phenomenon of mass-produced commodities “Made In China”.

Dean’s film, like Whiteread’s sun, is a big draw: daily crowds of people huddle together in the dark, sitting quietly on the concrete floor, watching the flickering images. Spanning floor to ceiling in the empty, echoing cavern of what was once the main turbine hall of a coal-fired power plant, the looped movie celebrates another vanishing technology: 35 mm photographic film.

“This beautiful medium, which we invented 125 years ago, is about to go,” she said. “How long have we got? I hope we’ve got a year left. It’s that critical,” she told the Guardian, which described her work as “an act of mourning and an argument for the future.”

So endangered is photographic film that the exhibit at the Tate almost didn’t happen. The staff at the Dutch studio that cut the film apparently introduced flaws into it, due to an erosion of the staff’s film-handling techniques; white flashes would have appeared throughout the film. A 52-year-old editor had to drive to the Netherlands in person to cut the film by hand with Dean and drive it back to London in time for the launch the next morning. Few professionals like him would have been up for the task, and there are fewer than a dozen labs worldwide which can print the medium. Manufacturing declines inexorably every year.

The virtues of working with film versus digital are debatable, but one thing isn’t: in an age when our lives are steeped in pixels, print media disappears from the shelves, and everyone gets a camera with their phone (and can bombard us with dimly-lit grainy images through Facebook), images created with traditional techniques can’t help but be striking. Photographers who never stopped using film have suddenly found found themselves back in vogue. For example, the 64-year old, Italian-born Parisian fashion photographer Paolo Roversi, whose contrast-heavy, dramatic portraits shot on Polaroid 8×10” are back in high demand after years of being obscured by younger photographers wielding new cameras and the latest software. Same goes for American art photographer Sally Mann, whose stark, haunting black-and-white images of the naked body are more popular than ever. Some, such as Edward Burtynsky, never went out of style, and remain giants of their trade. The revelation that his epic landscapes of bright orange rivers and rusting ships in muddy wrecking yards, are shot on film renders them far more impressive.

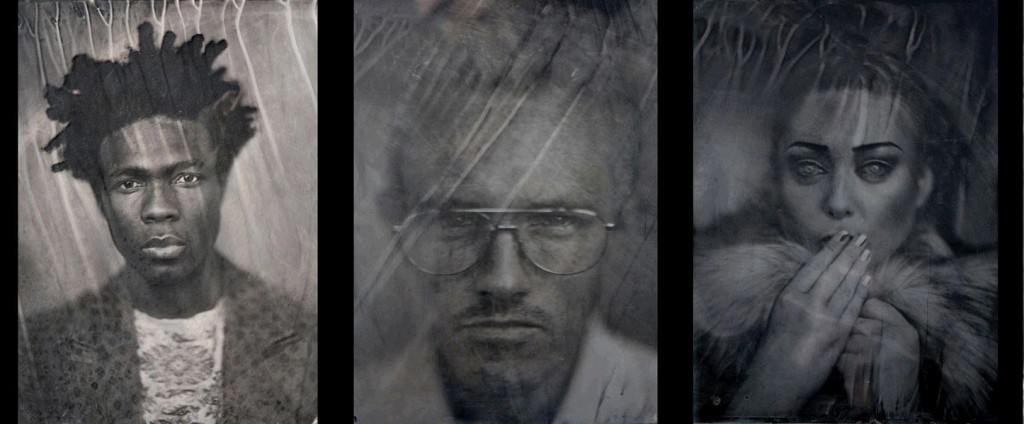

“No matter how much you re-touch a digital image, when you see it printed you can see that it has no integrity, and you know it’s not real,” says London photographer and street artist Walter Hugo. For him, working with film is a natural choice, because each frame is a “one off” image that can never be replicated, making it more of a tangible object. This year he has taken his work a step back even further, working with 19th-century lenses, and more recently, silver nitrate solutions, “resurrecting” the almost forgotten photographic techniques of the Victorians.

His portraits, created by coating concrete walls with silver nitrate solution, and using a battery powered projector to cast the image, have popped up as street art on buildings throughout east London and stand in stark contrast to digital photography. Most recently he exhibited his “photographic frescoes” at the Cobb Gallery in Camden.

This is the second in a tryptic of work that celebrates lost photographic techniques – the first being a walk-in camera obscura built earlier this year and exhibited at the Showstudio in Soho. Other artists in that show included the works of American photographer T. R. Ericsson, who created photographic silkscreen portraits using cigarette smoke in honour his mother, who died from her addiction.

Ericsson’s previous images are equally tangible in their materiality – other collections have included photographic images using powdered graphite on paper.

“The surface of a photograph is somewhat changeless, whereas the nicotine and graphite images appear unstable: smoke shouldn’t produce an image; an image trapped in powder should blow or fall away,” he says. “That’s the point for me: images are in fact unstable, their meanings are not fixed. They are secretive things, their meanings are always manifold. The materials I choose are meant to emphasize the unreliability of photographic images.”

While the norm of modern digital photography has become flawless, crisp, linear, flat images, now new forms of software are spreading that mimic traditional photography techniques, such as the three colour gum process, cyanotype and hand tints. If good for nothing else, the ubiquity of vintage-lens-effect iPhone apps betrays our thirst for the real thing.

“I think more traditional photographic processes are more inline with the way we see, feel and think as human beings,” says Hugo. “The digital is just so flat, blatant, blunt and generally unmysterious and unromantic. All photo-based everything is pure nostalgia. The old film stuff just does nostalgia better: it is dreamier, more filled with desire.”