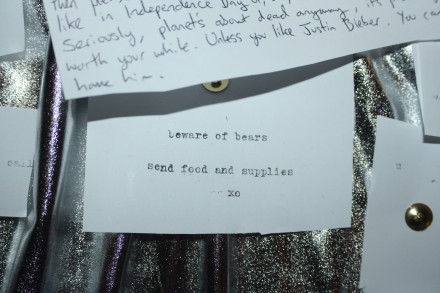

The first message bashed out on our vintage Underwood typewriter, pinned to the sparkly silver message board, set the tone:

“Beware of bears. Send food and supplies. Xo”

Most that followed struck the same chord.

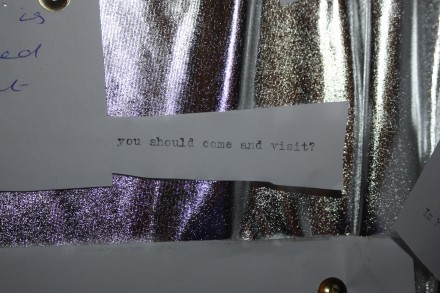

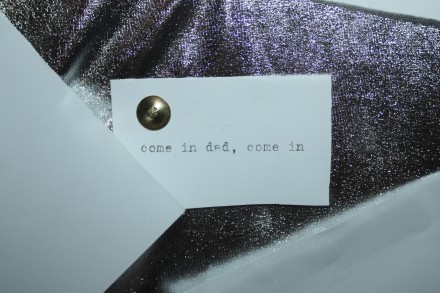

“We are here and we are having fun. Come and join us, come and join us, now.”

“So here we are, trying to talk to you, but you never call or write, what is that all about?”

Some chimed more in tune with current Zeitgeist.

“Are there any jobs out in space??? I am looking for work.”

Quite a few discussed (and apologised for) what’s on the telly.

“Hullo, Hope you’re well. Maybe you’ve seen some previous transmissions from our planet. Just to say, please don’t judge us too harshly for Hollyoaks. Many of us hate it. Ta muchly. Jim.”

“If Jeremy Kyle is your first experience of Earth, I am not sorry! We are not all crazy, I promise! ☺”

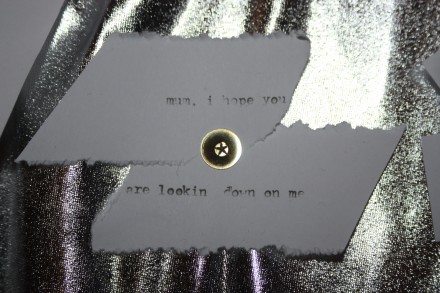

And a few were far from frivolous.

“Mum. I hope you are looking down on me.”

Each of the 47 messages left by our guests at the Astronomers’ Ball at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich said something, in its way, about the very odd thing that is the human condition. And every one will be sent into deep space from a parabolic dish antenna in Cape Canaveral, Florida. Using satellite broadcasting equipment with redundant high-powered klystron amplifiers connected by a traveling wave-guide to a five-meter parabolic dish antenna, owned and operated by the Deep Space Communications Network, these messages will travel for four years from Earth at a frequency of around 6,250 MHz.

Professor Izzat Darwazeh, head of the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering, donned his suit and tie, and joined us to explain to our costumed guests how radio waves will carry their messages into the deep unknown.

“What I found most fascinating is how interested people were. Astronomy itself is interesting to most people – but people were asking in general about my work, and about what do we do in communications engineering.” he says. “People from non-scientific backgrounds were asking quite sensible questions: ‘How could you send a message so far? Will these messages get anywhere? Would these be sent direct or through another mode? When might we get a message back?’” he says.

What would you say if you had one chance to speak to the stars? We still have plenty of space in the package that we will send out: email your thoughts to zoe@guerillascience.co.uk and we will add them to our interstellar chatter.

Remember, this is for posterity, so be honest. Those messages kept to a succinct 140 characters or less will be re-broadcast on our terrestrial Twitter feed. If so inclined, please record your microblog moniker with your note – who knows, our galactic followers may receive it. Alternatively, you can send us an illustration, as a few at the Astronomers’ Ball chose to. Or – if you are feeling extra communicative – you can send us a short video less than 20 seconds in length.

Will our message reach a receptive audience? And might we get a reply?

Almost certainly absolutely not. The sheer size of space, and the distance between the stars, reduces the chance of making contact to virtually zero.

Yet could there be intelligent civilizations out there – even some with the right equipment? Almost certainly absolutely yes.

As Jill Tarter, director of the Center for SETI Research (and the inspiration for Jodie Foster’s character in Carl Sagan’s Contact) argues in her TED talk, the number of stars that we have inspected, compared to all the lights in the universe, is equivalent to a glass of water in the sea. “And nobody would decide the ocean was devoid of fish on the basis of a single glass of water,” she says.

SETI, the search for extra terrestrial intelligence, has scoured the skies with radio telescopes for four decades, listening for signs of life – more precisely, the electronmagnetic transmissions that would be given off by a species with technological capacities like our own.

There have been some false positives: when the first pulsar was discovered in 1967 (the year of the summer of love no less), its rhythmic trills sounded so regular, astronomers concluded that it must have been created by artificial means fashioned by intelligent beings, and the cluster was deemed LGM – for little green men. You can hear it on the 8th track of the Guerilla Science Sounds of the Stars audio tour here.

But despite hope, and false hopes, all our listening has turned up nothing. But then, who are we to complain that the phone never rings, unless we dial up the networks ourselves? Contact will never be made if everyone simply listens.

The first deliberate attempt to shout a message to the stars took place exactly 37 years ago today, from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico, aimed at the M13 globular star cluster more than 25,000 light years away. This is still the strongest signal we have ever broadcast to space.

What on earth is a species to say in its first shout out to the stars? And in what language?

The now famous Drake message, crafted by astronomer Frank Drake with advice from science fiction writer Carl Sagan (author of Contact), went with the basics: the numbers 1 to 10, a graphic figure of our solar system, an outline of a human figure, chemical denotation of the elements that make up DNA, and so on – seven pieces of basic information to give a snapshot of our planet. Binary was the chosen tongue, because it lends itself easily to encoding: shifting the frequency of the signal up or down a notch could denote 1 or 0.

Exactly 1679 bursts of noise were broadcast – the number 1679 chosen because it is a semiprime number, the product of 73 by 23, which can be arranged into a rectangle to create the image.

This, our first message, will reach it’s target in 25,000 years – if received, and if a reply is made, we will not hear back for 50,000 years. Responders would need to not only have the equipment to receive the signal, they would also need to speak binary,and have the intuition to turn the 1679 notes into a grid. Not surprisingly, the intention was to demonstrate the technological sophistication of the equipment, rather than an earnest effort to make contact.

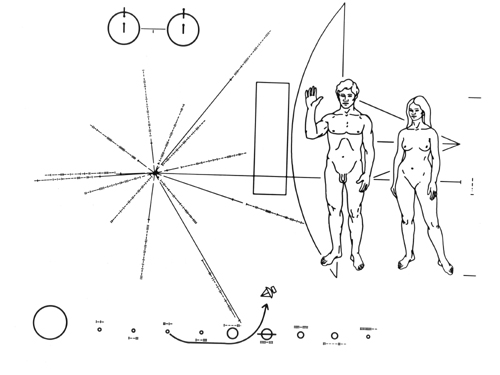

Symbolic or not, this was not to be the last snapshot of life on earth sent to intergalactic receivers: five years later the Voyager probes launched into space, with a more low-fi (and easily decoded) mode of delivery. It carries with it still a golden record of sounds and images of life on our planet, including whalesong and Mozart, Chuck Berry and string quartets, pictures of frogs, leaves, snowflakes, airplanes, people eating cheeseburgers, the moon, and this very famous image of a man and woman saying a friendly hello with a graphic of the origin of the probe – the third satellite from the sun.

This image, in fact, annoyed many representatives of half the human population: it is the male who waves, as though his status as interstellar ambassador is a given.

The female form however provides the first piece of information that finally reached another star: the sounds of vaginal contractions reached Epsilon Eridani in 1996. These were recorded and broadcast in 1986 by artist Joe Davis, who felt that all previous messages sent to space lacked depictions of human reproduction, and thus failed to really portray the human condition. These sounds, he felt, would best portray the essence of our species.

“If anything is going to inspire an alien civilisation to come running, surely that would be it,” noted Pigalle Tavakkoli of Contemporary Vintage, our guest that night.

There have been other attempts to craft universal messages. The “Cosmic Calls” in 1999 and 2003, sent from the Ukraine, broadcast what is known as the Interstellar Rosetta Stone – similar to the Arecibo message, but much larger, depicting the chemistry of DNA, the geology of the Earth, and basic mathematical principles. In 2009 Joe Davis broadcast the code for RuBisCo – the plant enzyme responsible for photosynthesis, and the most abundant protein on earth; not as salacious as the sounds of a ballerina’s vagina, but certainly an admissible ambassador for life on earth.

Some messages have been less philosophical: in 2008 Doritos broadcast a commercial for its nachos towards Ursae Majoris, the winning entry to an open contest for amateur filmmakers. The first ad sent to space, a stop-motion film of nacho chips performing a pagan ritual is, actually, rather impressive.

Nacho chips, prime numbers, plant enzymes and audible vaginas aside – is there any point in broadcasting our message to space? Many scientists would argue that it is a waste of time and energy. Others would go so far as to say that it is outright reckless, most notably Dr Stephen Hawking (a scientist so serious we might never expect him to turn his mind upon this subject). He very rationally argues that any civilization with the capacity to receive, interpret and respond to our messages will undoubtedly be far more powerful and advanced than our own – and likely to come here at all speed to harvest our resources. We might as well tweet “come and get us” into space.

But, the point remains: contact will never be made if we only listen. As Jill Tarter of SETI counter-argues: if there is intelligent life out there, and if we have the capacity to speak to them, we have a moral obligation to let them know that they are not alone.