Two dabs of conductant. A mouthguard, for your protection. Sturdy straps to secure you safely. A split second dose of electricity. And finally, a convulsive seizure lasting 15 seconds or more to trim the connections in your brain and erase the pain from your mind.

If you didn’t see us administering electroconvulsive therapy in the Secret Cinema’s rendition of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest this past November, you can see it in this short film. You may find it disturbing – many of our guests did.

Anyone who hasn’t seen One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest probably knows just one thing about it: the main character is subjected to shock therapy as punishment for his subversive behaviour. The image of Jack Nicholson chomping on a mouthguard, eyes clenched in pain and veins throbbing, is iconic.

No vision of electroconvulsive therapy is so famous. Nothing in popular culture has so profoundly influenced the way we perceive ECT, described in Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel as a dehumanising ordeal forced upon patients in a “filthy brain-murdering room that they call the ‘Shock Shop’”.

Before the pharmaceutical revolution in the 1960s and ’70s, ECT was practiced widely: it was one of very few therapies that could produce genuine, lasting changes in the mentally ill. It was lauded as a miracle cure: the Italian neurologists Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini were nominated for the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their work on the treatment in the 1930s.

It is interesting to note: ECT failed where the lobotomy succeeded. Portuguese neurosurgeon Egas Moniz won the Nobel Prize in 1949 for the transcranial lobotomy, a procedure that is now almost never performed.

Yet more than a million people a year undergo ECT today – though the experience now is very different from what it was half a century ago.

With advice and expertise from psychiatrist Dr Mark Salter, who coached our ‘patients’ Lime and Ramey, we staged ECT treatments (along with lobotomies) circa 1950 for two weeks straight.

We wanted to create the most historically accurate performance possible – even the machine we used dates from the era.

Many who passed through the Experimental Ward found the performance deeply disturbing, understandably. ECT is still performed today, and is still upsetting to many people. For some, it too easily brings to mind that horrific tool of capital punishment, the electric chair.

But proponents of ECT – and there are many, both doctors and patients alike – blame the film for permanently tarnishing its image. Though it may seem crude, it is “spectacularly successful” in treating depression, Dr Mark Salter tells us in this interview:

“We like to shoot the messenger, but the fact of the matter is that ECT if used in a model way, discriminately, and for life-threatening depression, is one of the most effective and powerful techniques in the psychiatric armoury today.”

The face of ECT now is far different from what one may have seen in a 1950s ward: muscle relaxants are used to immobilise patients and prevent the fractured bones and broken teeth that they once suffered, and a general anaesthetic ensures they will feel no pain and remember nothing about the experience.

Carrie Fisher – author and (yes) Princess Leia – has publicly championed ECT, which she says helped her with bipolar disorder: “It makes you feel better. They put you to sleep now. It’s not like it’s depiction in the media, which is really what caused the stigma. And I think a lot of pharmaceutical companies are not so happy [about it] because it works so well.”

Psychiatrist Dr Maurice Greenberg tells us just what it is like to administer the treatment in this audio recording.

Nonetheless, there is something deeply unsettling about ECT – to many medical professionals as well as patients. As Dr Greenberg tells us, one colleague in particular “refused to give it on principle… he argued there was no real evidence to justify its use.”

That was back in the 1970s, when very little was known about how ECT actually affects the structure of the brain. Delivering a shock of electricity to force a seizure, without understanding the true consequences, seemed to many physicians to be reckless, barbaric, and inhumane. All patients who undergo ECT – then and now – experience memory loss, sometimes to a severe degree, a side effect many patients find deeply upsetting.

The patient Harding tells RP McMurphy what the experience will be like, in Kesey’s 1962 novel:

McMurphy: And you say it don’t hurt?

Harding: I personally guarantee it. Completely painless. One flash and you’re unconscious immediately. No gas, no needle, no sledgehammer. Absolutely painless. The thing is, no one ever wants another one. You … change. You forget things.

It is indeed true that ECT was used as punishment by some hospitals, as McMurphy experiences in Kesey’s novel. Even more common, it was doled out therapeutically but indiscriminately, administered to patients suffering from conditions that it could not help, such as schizophrenia, learning disabilities and even epilepsy itself.

Lou Reed was subjected to ECT in the 1950s to “cure” his homosexuality, an experience he describes in Kill Your Sons (1974):

All your two-bit psychiatrists

Are giving you electroshock

They said, they’d let you live at home with mom and dad

Instead of mental hospitals

But every time you tried to read a book

You couldn’t get to page 17

‘Cause you forgot where you were

So you couldn’t even read.

Sylvia Plath also underwent ECT, in her case for severe depression and suicidal desires, which she also describes in poetry.

By the roots of my hair some god got hold of me.

I sizzled in his blue volts like a desert prophet.

The nights snapped out of sight like a lizard’s eyelid:

A world of bald white days in a shadeless socket.

A vulturous boredom pinned me in this tree.

If he were I, he would do what I did.

– The Hanging Man”, 1960

Ernest Hemingway also received ECT for severe depression. We do not however know much of what he had to say about the experience – his capacity to write was virtually destroyed by the treatment, and he committed suicide shortly afterwards.

ECT has persisted as a course of treatment since it was first used in the 1930s – virtually the only medical treatment from that era still in use today – and millions of people credit it with alleviating their severe depression, and ultimately saving their lives.

It is undeniably remarkable – from a biological point of view – that inducing an epileptic fit by sparking the brain with a brief pulse of electricity can alleviate depression, improve mood and change disposition.

But of course, this beggars the question: who in their right mind would conclude in the first place that seizures should be induced as a medical treatment? How could a convulsive fit help a sick person get better? As the epileptic patient Sefelt puts in, in Kesey’s novel: “What a life – give some of us pills to stop a fit, give the rest shock to start one.”

Medics had observed since the 19th century that schizophrenics tended not to have epilepsy, and vice versa. It was mistakenly believed that the two conditions were antagonistic. So it seemed reasonable: perhaps artificially inducing a seizure could alleviate the symptoms of schizophrenia? Hungarian Ladislas von Meduna tested this hypothesis by inducing seizures in schizophrenics using the notorious and now banned medication Metrazol, before Cerletti and Bini brought in the use of electricity.

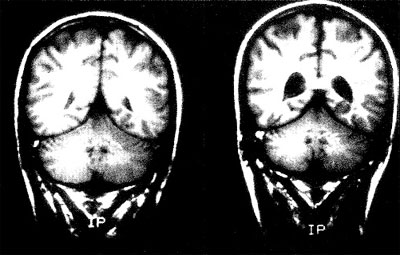

The hypothesis turned out not to be true: schizophrenia is not “antagonistic” to epilepsy, so to speak. Epilepsy involves waves of electrical activity spreading through the brain – almost like explosions. Schizophrenia on the other hand involves anatomical changes, and can be spotted almost at a glance in MRI scans: ventricles – the fluid filled spaces within the brain – are much larger in schizophrenics.

Nonetheless, we now have evidence to support the idea that seizures can be used therapeutically. Modern research in rodents seems to show that ECT works by pruning the connections between neurons in the hippocampus, a portion deep in the temporal lobe of the brain involved in memory formation and mood. It seems that the production of neurotransmitters – chemical messengers that the brain cells use to “talk” to each other – are then reset and recalibrated.

Interestingly, it seems that important changes are brought about in the secretion of serotonin, noradrenaline, and other messengers that are targeted by antidepressants. Some studies show that in fact ECT has an even more dramatic effect on these neurotransmitters than pharmaceutical medications. Neuroscientists are still working out the details, but it seems that ultimately a boost is given to the production of “growth factors” – chemicals that foster the growth of new nerve cells.

The end result: new connections are forged in the hippocampus, a region of the brain that seems to shrink in severely depressed people. By pruning down old connections and forging new ones, ECT could almost be thought of as administering a kind of neural renovation.

For many individuals, as a last resort for suicidal thoughts, depression, catatonia, psychosis and bipolar disorder, the therapy has succeeded where all other treatments have failed. As a last resort, it can truly be life saving – despite the costs.

If all else failed, would you choose to burn away the connections in your mind if it took the pain away?