If you passed through the experimental ward in the Secret Cinema’s fortnight of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest this November, you may have come across a young physician in a clean white lab coat instructing a group of medical students under a humble chalkboard:“LOBOTOMY TECHNIQUES, PAST AND PRESENT, 1935 – 1962, for the alleviation of psychosis, delusions, and emotional distress.”

Coupled with a soliloquy on the virtues of the frontal lobotomy, an ice pick was gently jammed into the eyes of a polystyrene head, and swirled through the frontal lobe of the dummy brain, severing connections between the foremost structures of the cerebrum and the medial structures in the interior. A rigorous twirl produced the most marvellous squeaking.

Catch a glimpse of our lobotomy class in this short film, starting at 2:30. Or enjoy the procedure in Russian at 2:45 in this TV news segment.

Our demonstration – disturbing to some, hilarious to others – may have seemed grotesquely comical. But every single thing we said was absolutely true.

It is indeed the case that the transcranial lobotomy, refined in Portugal in the 1930s by the neuropsychiatrist Egas Moniz, gleaned its inventor the 1949 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Perhaps, if you knew this already, you could have answered correctly the question posed by our medical instructor: What do Albert Einstein and the transcranial lobotomy share in common?

Though it may seem absurd now, the frontal lobotomy was indeed regarded as a medical marvel in the middle years of the last century – it was lauded on the front page of the New York Times in 1937 as a breakthrough “Surgery of the Soul”. Some 40,000 people received the procedure in the 1940s and 1950s in America, and another 10,000 in Europe.

The prefrontal lobotomy stood alone among medical procedures in its ability to permanently modify the mentally ill: the ‘incurably insane’, violent individuals suffering from severe psychosis, were rendered placid, gentle and uncomplaining. Moreover, sensory and motor functions – the ability to move and feel – could be left largely unaltered, while disposition and temperament were utterly transformed. Violent tendencies evaporated, and suicidal thoughts disappeared.

But as miraculous as it seemed, the transcranial lobotomy had practical drawbacks: it was messy and intensive, requiring two unsightly holes to be bored into the sides of the skull. It required a fairly intensive hospital stay, with a great deal of postoperative care.

On occasion, it resulted in tragic consequences: patients could be rendered mute and immobile. Humans became vegetables. The most famous case: Rosemary Kennedy, sister of John F, who underwent a transcranial lobotomy in 1946 at the bequest of her father for her extreme “moodswings” (the true nature of her mental condition before the operation remains highly contested).

As they bored into her skull, Kennedy’s surgeons asked her to count backwards, and to recite phrases she knew by heart, so they could calculate if they had penetrated sufficiently far into the brain – including the words to God Bless America: “Stand beside her, and guide her / Through the night with a light from above.”

Unfortunately they went a touch too deep, and Miss Kennedy spent the rest of her life without the ability to speak or control her bladder. Considered the first “Kennedy tragedy”, she was kept largely out of the public eye, a great embarrassment to the family. She died in 2005.

Her surgeon, Walter Freeman, was dismayed by the event – yet still resolute in his determination to perform what he considered to be a miraculous procedure.

Could there be a better way? Cleaner, gentler – perhaps cheaper as well?

He hit upon the solution: an icepick.

Rather than reaching the brain by going through the top of the head with a drill, why not access the cortex from the opposite direction, through softer tissue: from the bottom?

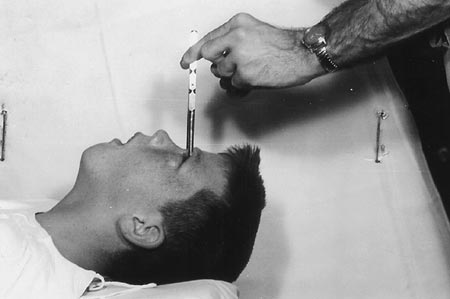

Thus Freeman developed the transorbital lobotomy: it was this technique that revolutionised the procedure, and which we taught to our medical students on those chilly evenings in the Secret Cinema. It is this operation that RP McMurphy receives at the end of Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – an “installation”, as it is dubbed in the book.

The appeal of the transorbital lobotomy is that it can be done very, very quickly: in just ten minutes. The patient may be sent home that same evening in a taxi cab. No anaesthetic, no bloody mess, no unsightly scars – only two black eyes. The operation became, in effect, a simple office procedure.

The procedure is simple: after immobilizing the patient with electroshock, simply insert an icepick under the eyelid, slide it over the eyeball, tap it through the roof of the orbit with a hammer, and insert it roughly five centimetres into the white matter of the brain (the connecting portions of the neurons). Then simply swirl it around to sever the connections. According to Mr Freeman, the ideal manoeuvre is to imagine that one is “beating an egg”.

Want to see for yourself? Have a look at this short instructional film produced by Freeman himself. Be warned: the content is extremely graphic.

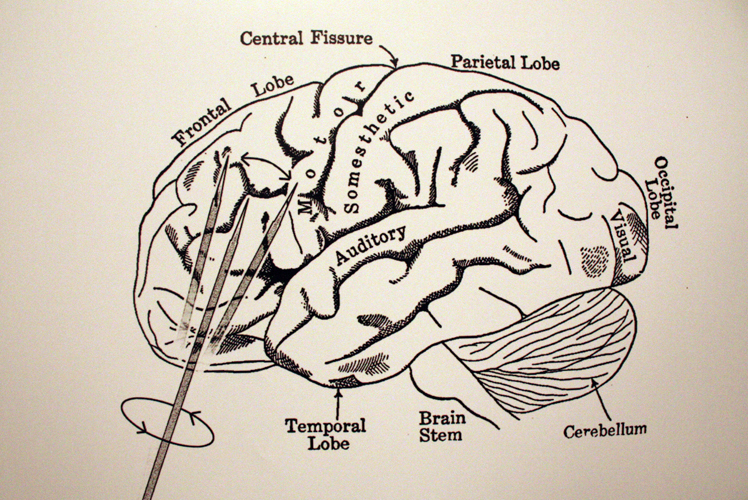

Freeman’s theorising – as explained in this first portion to his instructional video – seemed to make intuitive sense. The most ancient parts of our brains are located at the bottom and in the middle – such as the brainstem, hypothalamus, cerebellum, and the structures that make up what we call the limbic system. The newer parts lumped on top and around the old regions – in particular, the cortex, the wrinkly surface of the brain.

The newest and most fully developed in humans compared to animals – that part which one might say most makes us human – is located right behind our forehead: the frontal cortex. This is the region we most associate with reason, higher thought, and self-control.

Freeman believed that an excessive number of connections between the frontal portion of our brains and the older, more “animal” structures – in particular, the thalamus – were to blame for many symptoms of mental illness: an excessive influence of emotion upon intellect.

So the solution was simple: cut those connections.

By simplifying the procedure, Freeman revolutionised the frontal lobotomy. More than 2,500 Americans went under the icepick with Walter Freeman and his transorbital technique. By 1951, more than 18,000 individuals had been lobotomised in the US (both transcranially and transorbitally), thanks in large part to Freeman’s popularisation of the procedure.

Of course, he didn’t simply ram ice picks into the brains of hapless patients. He practiced first: on grapefruit. According to his son Frank, he perfected his technique on a carload of fruit, using an icepick plucked from their kitchen cupboard.

Freeman was not only a physician, but also a showman – a one-man lobotomy roadshow. He went across American, performing lobotomies on as many patients as he could fit into a day, to broadcast its simplicity and versatility. His record number: 25 women in a day, 228 individuals in a month.

Freeman’s greatest innovation was to broaden the diversity of patients for whom a lobotomy could be prescribed. Originally, it was thought of as a miracle cure for the incurably insane. But under Freeman’s guise, it became a panacea for a whole host of emotional and mental conditions: anxiety, depression, OCD, post-natal depression. Even severe headaches could be alleviated with a simple transorbital lobotomy. Children too, he claimed, could benefit: hyperactivity and poor behaviour would improve following a twirl of his ice pick. He operated on 19 children under the age of 18. The youngest? Four years old.

The most famous child Freeman operated on is still alive: Howard Dully, now a middle-aged bus driver in California, who received a transorbital lobotomy in 1960 at the age of 12 for behavioural issues:

He objects to going to bed but then sleeps well. He does a good deal of daydreaming and when asked about it he says ‘I don’t know.’ He turns the room’s lights on when there is broad sunlight outside.

Dully discovered these notes and far more when he sought to uncover why he was lobotomized – a story that is told in a fantastic documentary produced by the American station NPR. Have a listen here.

“I’ve always felt different – I’ve always wondered if something was missing from my soul,” he tells us.

In this uniquely illuminating story, we meet the first person to receive a transorbital lobotomy, Sallie Ellen Ionesco, who describes her physician as “a great man” – he cured her of her suicidal rages. Like many of Freeman’s patients, she retained many of her verbal and mental faculties, and genuinely believed the procedure had saved her life.

But we also meet some tragic cases, including Anita Welch, who was lobotomised by Freeman for postpartum depression – and spent the rest of her life in mental institutions.

If you have twenty minutes to spare, give this documentary your time. You will spend the rest of the day glad you are you.

Naturally, one is left wondering: Who on earth would allow a surgeon (an ungloved one at that) to stick an ice pick up through their eyelid, right into their brain? Perhaps the only thing more shocking than the methodology of the transorbital technique was its popularity: ‘fully functioning’ members of society, with jobs, families and relatively ‘normal’ lives, lined up to be lobotomised by Freeman for all manner of complaints. Sometimes on multiple occasions. His last patient – who died from a brain aneurism on the operating table – had come for her third procedure.

Though at first blush, Freeman appears monstrous and power-hungry – the archetypal mad scientist – it is important to remember that he is said to have genuinely believed this was a beneficial, transformative and life-saving procedure. The original lobotomy had, after all, received the Nobel Prize. At the time of its development, there were no drugs that provided lasting relief to the suicidal, the delusional, or the depressed – only nefarious and now banned treatments such as the notoroious Metrazol.

The history of psychiatry has seen many other controversial and brutal treatments – from insulin comas, to workhouse asylums, to straightjackets. Yet few inspire such revulsion as lobotomies, with good reason: the technique was designed to mangle that very part of ourselves that most makes us human.

But this story, like any study of history, leaves us with an interesting question: what medical procedure or prescription that we now consider acceptable – even routine – may we one day regard as barbaric?