How can you give the things we buy new life rather than dumping them in landfill (or worse still, letting them wind up in the ocean)?

There are three solutions commonly used by companies at present:

- Recycling: turning something into the same form of itself (which is easy for things like plastic bottles)

- Downcycling: transforming a product into an inferior one, such as grinding running shoes down to create the surface of basketball courts

- Upcycling: converting a product into a superior form, such as spinning single-use plastic bottles into polyester fabrics which might be worn for decades.

Despite their best intentions, all these methods create waste at some point in the manufacturing process, from the pesticides and fertilizers used to grow crops such as cotton, various pollutants in the wastewater from the factories that make them, greenhouse gas emissions or heavy metal emissions from the energy source and so on. The more you examine the entire lifecycle of a product the more you realise that waste is always created somewhere.

But what if you could design something so was no waste is created at any point whatsoever? Enter “Cradle to Cradle” manufacturing, a vision of how we could and should make things, everything from shoes to shirts to factories to cities.

The concept was devised initially in the 1970s as a play on the phrase “cradle to grave” and was later formalised in the best-selling book of the same name, penned by design chemists Michael Braungart and William McDonough. The simple strapline: “Re-making the way we make things.” Today the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute (C2CPII) certifies thousands of products, ranging from tyres to carpets, soap to construction timber.

The core Cradle to Cradle concept is to model industrial processes on natural ones – what is known as the “biomimetic” approach. In the natural world, there is no such thing as “waste” – everything is recycled down to every atom. Ambitiously, the C2CPII says its ultimate goal is to see consumer products as “nutrients”. As an example – department store C&A’s solid Gold Level Certified T-Shirts that can be safely composted.

It’s an ambitious concept and requires an enormous amount of careful thinking, tinkering and designing in the formation of any product: every single manufacturing step must be re-thought to ensure that not only is nothing wasted, but that every single component is fully biodegradeable and nontoxic. Stringently, they test every chemical or ingredient that could be used – solvents, dyes, emulsifiers, cleaning agents, you name it, and keep a library of those approved to be safe enough for human exposure or environmental release.

For years manufacturers of furniture, lightbulbs, paints and more have sought certification of their products and made use of the chemical library. Now the institute has an launched an initiative focused on what we wear: Fashion Positive.

Though fashion may seem trite compared to, say, furniture or food, it is anything but, says Emma Williams of C2CPII, pointing out that the World Resources Institute estimates the fashion industry employs more than 300 million people worldwide, is a $1.3 trillion industry, and the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles or clothing is burned or landfilled every second.

“It’s really fascinating to consider, because when you wake in the morning and get dressed, you never think about that,” she says. “In a strange way, perhaps because clothing is always so close to us, or maybe because our identities are to some degree connected to it, we perceive it differently to the way we things such as automobiles.”

Plus, the combination of “fast fashion” with its micro-seasons, and the growing middle classes in the developing world means that the production of textiles has doubled in the past 15 to 20 years she says – making the environmental impacts all the more important.

A big part of the work at the institute is to promote the sharing of ideas, materials, and processes – a vast departure from the old-school concept of “trade secrets” kept closely guarded at high-end firms. Working with the institute the Fashion Positive PLUS collaboration includes H&M, Kering, Stella McCartney, Eileen Fisher, Athleta, Loomstate, Mara Hoffman, G-Star RAW and Marks & Spencer, who are all working together to identify commonly-used high-impact “building block” materials such as yarns, dyes, and finishes.

This is all part of a wider trend of sharing knowledge for the greater good. After spending 10 years developing a high tech, super-efficient and new way of producing t-shirts at their factory (using organic inks and clean tech), fashion brand Teemill has taken things even further by creating the first fully circular t-shirt.

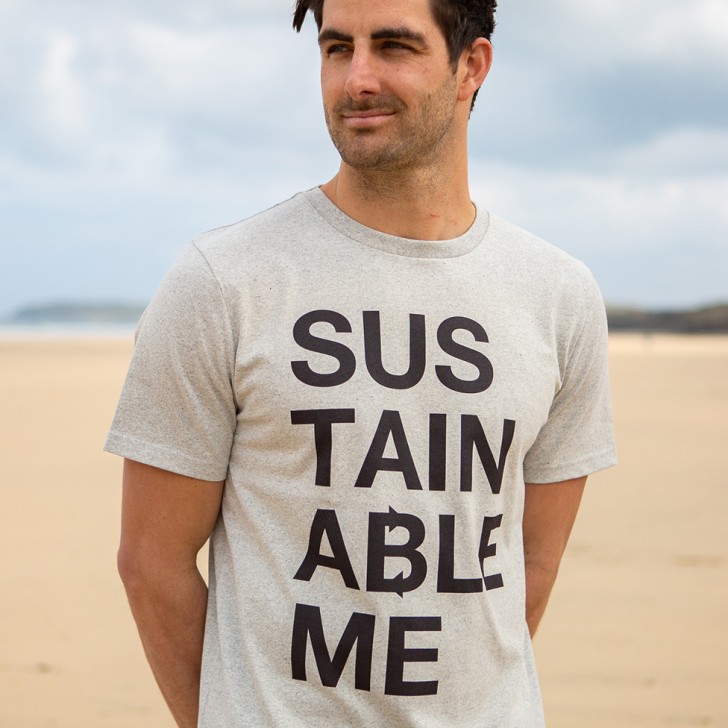

The zero waste ‘Sustainable Me’ t-shirt is made by recovering and reusing discarded organic cotton garments mixed with certified cotton and is designed to come back to Teemill once the customer is done with it, where it can be broken down and turned back into another t-shirt.

As with the rest of their products, rather than producing huge batches of t-shirts and pushing them onto consumers through advertising, they only produce clothing to order. The innovative printing presses they have make this cheaper and more efficient than bulk production which ultimately leads to excess stock.

“It’s nice that one brand might do something, or that everybody might do their bit, but sharing the technology we spent 10 years developing is key – now others can replicate it in 10 minutes,” says Mart Drake-Knight of Teemill.

And like the C2C concept, they have organised their production to recycle their t-shirts back into the exact same t-shirt. “Our products are designed to be sent back to us – we decided to see our supply chain as a connected system, instead of us just being the middle man in a linear chain of manufacturers and recyclers,” he says.

How do they do this? By rewarding customers for sending their shirts back to them – cheaper than spending money on advertising. “We pay the customer to give us a return, but from our view, we’ve just gotten free fabric,” he says. “It’s an economic trick.”

It’s all part of the same concept as the Cradle to Cradle movement:

“Certainly the hardest thing to get your head around is the fact that there is no such thing as waste,” he says. “This is not an incremental design challenge, but a whole life cycle design challenge. But with modern technologies, it’s easier than you think.”